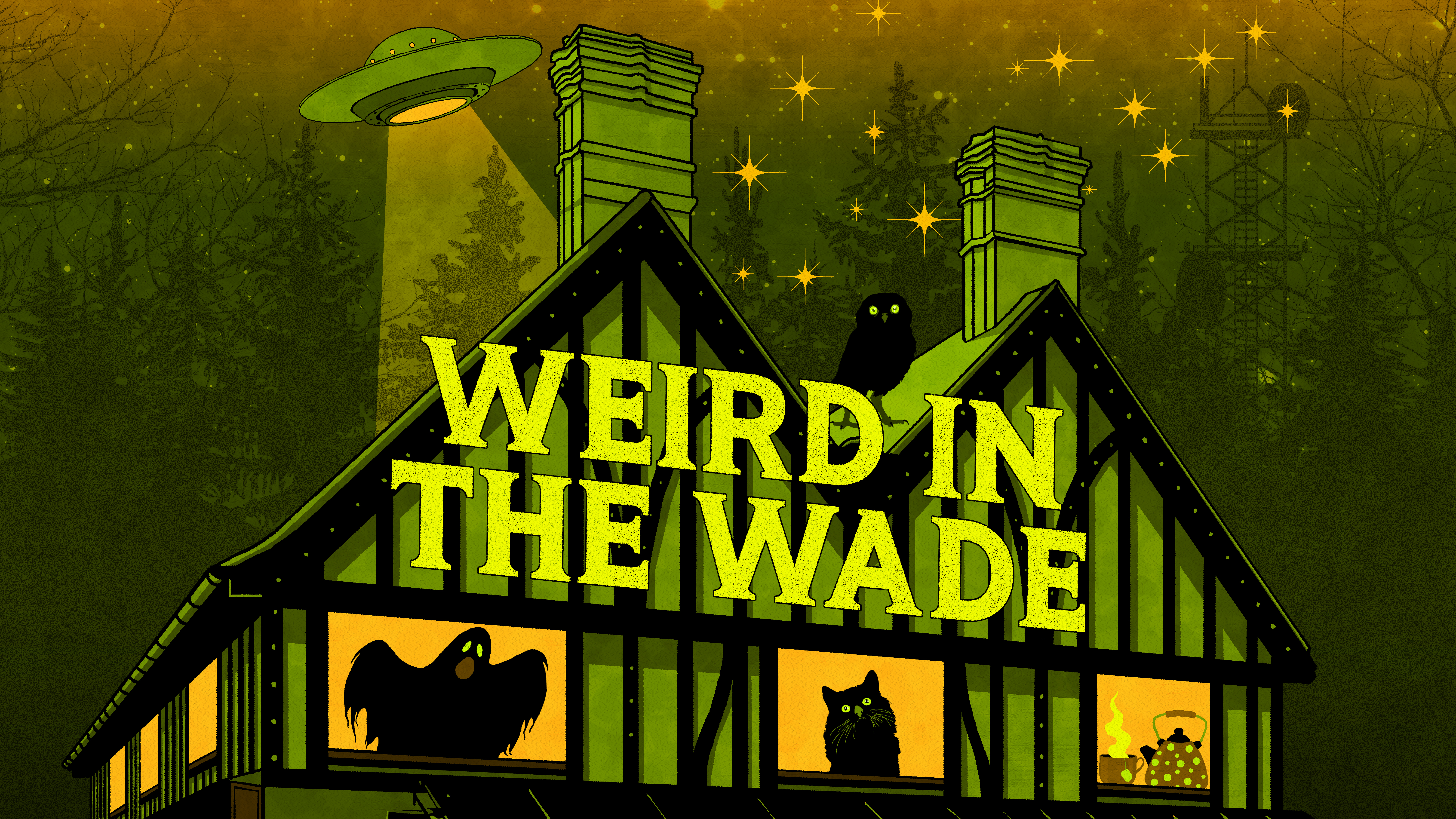

Listen to Weird in the Wade here.

Dramatic Introduction: Murder Bridge

It’s 1960, a warm Saturday evening, springtime. We’re on Biggleswade common up near the hospital, the south side of Potton Road known as the pastures. Children have been playing here for most of the afternoon. Fishing with colourful nets in the stream, building dens amongst the trees, lying in the grass dreaming.

As dusk draws around us, most of the children have left for home. Left before the streetlamps flicker on. But not Keith, Martin, nor Carole. They’ve lied to their parents about where they are. Keith and Carole’s Mum thinks they’re both with Martin’s family, Martin’s Mum thinks he’s at Keith and Carole’s. They’ve dreamt up this ruse so they can go on a dare.

They’re waiting for the dark to deepen, for night to set in. Waiting for the common to be swathed in shadow.

“No torches” says Keith, he’s the eldest at 12, Martin is his best friend is 6 months younger. Carole is 10 but braver than both boys.

“No torches” they all agree.

Now that it’s dark the half-moon is bright enough for them to see their way across the lumpy grass.

The cows are grazing at the other end of the pastures, away from where the children are heading, but the cattle’s occasional lowing and movements are making the children nervous.

“It’s just the cows” says Carole

“Just the cows” the boys agree.

As if by some unspoken agreement they all stop at the same time. They’re not far now.

“We go together.” Martin says

“Agreed.”

“We leave together” Keith says

“But you mustn’t run!” Carole interjects “because if one of you gets spooked and runs for it, we don’t all have to follow? Right,”

The boys sound less sure as they agreed. “Right.”

Again, without speaking another word they all set off at the same time. Taking slow and steady steps. Carole’s heart is thumping, but she is not going to let her brother nor Martin know that she is scared.

She can see it now, ahead of them. The brook is to their right, it’s no longer the shallow sided stream the younger kids had been fishing in earlier. Here the brook is at the bottom of a steep sided ditch, the water unseeable unless you lean over and peer in. It runs silently under the road through a tunnel. When you are on the road above you have no idea you are travelling over the ditch. It is a bridge, but it doesn’t feel like one at all. Only from down here in the pastures can you see that the road forms a bridge.

There are bushes and dark grass obscuring the view under the road. There’s been no traffic for the last 5 minutes.

The bird song dwindled with the light. All Carole can hear is her heart beating and the breathing of the boys. They, are definitely scared.

Martin had reminded them of the story that afternoon whilst the sun was still shining, and the dare seemed far away in the future.

“It’s called murder bridge because back in the war, a young nurse was murdered there. Her body found stuffed under the bridge in that ditch. Found by children like us out playing. But the children were so scared they didn’t tell anyone about her body. And she lay there for another week until an old fella found her whilst walking his dog. The dog barked and barked until he went and looked. They say the old fella’s black hair turned white overnight with the shock.

Her ghost hates children, because the children left her there, she blames them. She appears like a grey shrouded mist at first, then her phantom takes shape, and she wears a grey nurses cape, and she flies at any children who approach, screaming and cursing at them! That’s why you must never cross the murder bridge at night, and you certainly should never approach the bridge from the common.”

“Who’s actually seen her then?” Carole had asked wanting some firm evidence.

“Malcolm Wright did last year. And Donald Carver saw her with a group of other kids in the summer of 57 he works with my dad now and told him all about it.”

Carole doesn’t trust Malcolm but she does trust Donald, he’s practically a grown up now.

Now we are just a few yards from the bridge. They stop again, and peer at the ditch, at the long river grasses which are swaying ever so slightly in a chill breeze, the children listen. Nothing. Just the night.

Carole steps forward, determined to get as close as she can. To prove the boys wrong. But her approach is cut short, just a few feet away from the bridge, from the black mouth gaping below the road. She stops because of the sound.

At first, she thinks it’s the bark of a dog.

Like the dog in the story Martin told, the dog that found the body. She freezes, holds her breath.

Then the noise sounds again along with some rustling, the noise is coming from the ditch. It’s a fox surely. She breaths out.

Then out of the ditch just in front of the tunnels dark maw, looms a huge grey shape. She hears the boys behind her scream. She gasps, frozen to the spot.

The grey shape is wide, like a person wearing a cape, with thin legs almost dangling below, the cape wafts, the figure takes off into the air in front of her, screeching and growling. There is a rushing sound, a flapping, a flapping of wings.

The relief. She has never felt such relief as she swivels to watch the heron fly over her head and over the boys who are pelting away from her screaming and crying like the silly cowards, they are she thinks.

“It’s a heron you idiots!” she calls after the boys “A bird! It’s just a bird! The phantom of the murder bridge is just a silly old bird.”

The boys have stopped some way away from her, they are doubled over catching their breath, laughing shakily.

Carole turns to look over her shoulder, she’s not sure why. The dark opening of the bridge is blacker than the night around her. She shakes her head, she’s about to look away but out of the corner of her eye she sees a mist rising, curling like breath escaping the tunnel’s black mouth. She blinks. And it’s gone.

She hurries to the boys who have now switched their torches on and are searching the skies and the grass in front of them for the bird that gave them such of a fright.

“Let’s go home.” Carole says determinedly.

Welcome

Welcome to Weird in the Wade, I’m Nat Doig and today’s episode is about ghost stories and hauntings that are associated with crime. After last month’s highwaymen episode, it struck me that many ghost stories have connections to either criminals or the victims of crime. I want to explore that idea a little further in this episode and the following episode so this is a two part exploration of criminal phantoms. And as it turns out, Biggleswade’s most notorious haunting is associated with a crime. But before we return to that, just a heads up about what else is in store for you in this episode.

I have a very special guest. Wayne from the Eerie Edinburgh podcast and YouTube channel joins me for a discussion about crime and hauntings. I asked Wayne not just because I love Eerie Edinburgh, links to the show are in today’s show description, show notes, blog and social media. But because a lot of the Scottish ghost stories he has told do have an element of crime in them. I thought he was the perfect person to ask about this particular genre of ghost story.

We’ll also return to Black Tom and examine whether the outlaw Thomas Dun could be Black Tom’s companion phantom? He was described as one of the wickedest men who ever lived. This is just part one of a two episodes looking at hauntings and crime. In the next episode we’ll look at body snatchers in Biggleswade, ghostly graveyards and a victim of crime who haunts Green Park in London. Stick around to the end to find out more.

So, they are going to be two episodes jam packed with ghostly crime from Biggleswade, Bedford, Bedfordshire, London and Scotland! We’re going on a real journey across the country so buckle up and enjoy the ride!

And if you do enjoy Weird in the Wade there are some ways you can support the show. Please do tell your friends and family, your social networks about the weird in the wade if you can. You can also rate and review the podcast on some podcast platforms, apple and spotify for example. When you leave a rating or review it means more podcast listeners will see the show! And I really want to say a huge thank you to all of you who listen because so many of you do, Weird in the Wade is consistently in the apple podcast charts for history podcasts! It honestly blows my mind that my little podcast reaches so many of you and that you enjoy it. I can’t explain how happy that makes me! It’s almost a year since I started the podcast and there will be some exciting news about podcast developments before the first year anniversary in May. Think merchandise and a patreon! There is one other way you can support the podcast, if you can afford to buy the show a coffee or two, I have a ko-fi page ko-fi.com/weirdinthewade where you can do just that. All the money I raise goes back into the show, paying for podcast and website hosting, music licensing, equipment, travel costs and buying my guests a coffee and a slice of cake!

But back to today’s stories.

The Murder Bridge

Now surely the Haunted Poundstretcher is Biggleswade’s most famous ghost story, I hear you say. Well thanks to Damien O’Dell’s books and Weird in the Wade it might just be. But if you’re a local to Biggleswade the ghost story you probably think of first when asked, does Biggleswade have any ghosts, is that of the spirit that haunts murder bridge. In fact, it’s so well known that most people roll their eyes when anyone mentions it. Murder bridge is a local cliché. Just about every kid who grew up here, knows the story and knows not to go past or over the bridge. It’s one of those geographical boundary ghost stories. That maybe served the purpose of stopping kids from wandering too far from home.

The general gist of the story is this. The bridge on the Potton Road, right at the far north eastern corner of the pastures side of Biggleswade common is called murder bridge because a poor young nurse was murdered there in the second world war and her ghost now haunts the spot.

But even the bare bones of this story are disputed. Some say the actual murder bridge is a bridge called Mill Brook bridge just along the Potton Road nearer to the ancient hamlet of Sutton. This Mill Brook bridge is just before or after a sharp bend. The bend is also often called murder bend. Many nowadays assume that murder bend gained its name because it’s “murder to drive round it” though that seems a bit of a stretch, as it’s not that bad of a bend nor do there seem to have been a disproportionate number of accidents there.

But I’ve always heard that murder bridge is the bridge nearer to Biggleswade hospital. Biggleswade History Society did some digging in the 1990s but couldn’t answer the question definitively.

Sadly I can find no witnesses who say they’ve seen the ghost, yet every kid knows that there is one. If you’re local and you have seen the ghost or know someone who has. Please do get in touch. Contact details are in the show description wherever you’re listening now.

The first reference to the bridge being called “murder bridge” that I can find is in a Biggleswade Chronical article from 1950 about a car driving off the road there on to the pastures or meadow next to it. The article shows that clearly by 1950 which ever bridge it is, it was well known as murder bridge locally.

I looked for a murder associated with the bridge and also came up empty. I looked for any murder victim being reported found at that site or on the common, or on Potton Road but found nothing. In fact, murders in Biggleswade were few and far between. And none matched the description attached to our story.

I found a poor victim of a famous highwaymen gang who was murdered on a road a mile from Biggleswade. Killed for a few pennies and his watch. This was in the 18th century, and it doesn’t specify which road, so it’s unlikely to be at our murder bridge.

I also found an accidental death in a ditch on the common, but it was of a man in his 40s who was gathering watercress, he slipped and hit his head. No exact location is given for this death either and the common is large stretching around the northern half of Biggleswade.

All other murders took place in homes, pubs or just didn’t fit the description, and there are thankfully, as I already said surprisingly few Biggleswade murders.

But there is one contender for creating or inspiring this story, though it is a tenuous link as it didn’t happen in Biggleswade.

A war time murder

In 1943 Muriel Gertrude Emery, just 21 years old was working as a nurse at the three counties hospital, which although a mental hospital in the old Victorian asylum style, was being used as an emergency hospital during the war. The three county’s hospital was situated 8 miles due south of Biggleswade between Arlesey and Stotfold. Muriel was still a probationer and had trained it appears at the London Royal Free Hospital far from her home county of Norfolk. She was brought up by a single mother, Mildred Emery who must have been immensely proud of her daughter’s work during the war.

On the evening of the 18th August 1943, Muriel on a break from work, met with her boyfriend in the grounds of the hospital. After saying goodbye to him and turning to head back to work she was set upon and brutally murdered. Her body left in a nearby spinney.

In spite of the involvement of Scotland Yard in the investigation, Muriel’s murderer was not caught until 6 months after the crime. Reginald Waler Rowley, though living in Stotfold was reported to have been from Biggleswade. He was 24 years old, and a farm laborour. He was caught after attacking a shopkeeper in her 60s. He confessed to Muriel’s murder and was spared the death penalty at his trial due to having epilepsy. It was argued that the epilepsy diminished his responsibility. He was sentenced to hard labour instead.

I link this story to the murder bridge, purely because it is an actual murder of a nurse that took place nearby during the war. Though I can find no link between Muriel Emery and the hospital at Biggleswade, the initial court hearings and inquest were held in the town so the people of Biggleswade would have been very aware of it. Biggleswade hospital is very close to the bridge known as murder bridge.

Why would this tragic murder, which was headline news across the country, inspire the murder bridge tale you might well ask?

Maybe the ghost story is a fragment of social fear. A fear about being out alone, near to the hospital. Many nurses will have been travelling to and from Biggleswade hospital along Potton Road, or even over the common, in the dark on foot or bicycle. There was at least 6 months with no culprit identified and other attacks on nurses were happening across the country. And the country was concerned about this, unprecedented numbers of women were traveling by themselves late at night and early in the morning to attend work. Not just nurses, but often the hospitals and old houses being commandeered as hospitals were far from the centre of town, just like the three counties and Biggleswade hospitals were back then. Many of the women, like Muriel were in places unfamiliar to them because of the war. They were on foot or on bicycles so did not have the protection of a car.

For any man intent on attacking women, these lonely hospital grounds and environs provided the opportunity. The war itself and the increase people coming and going because of the war as well as the strain on resources gave a greater ability to escape the law. And even in 1958 another murder at the three counties hospital of a young nurse, was partly blamed on the lack of street lighting and safety for those travelling to and from the site.

So, I do wonder if the murder bridge ghost story, is a mix of half remembered fears. Fear associated with lonely places near to hospitals. The fear that parents want to instil in their children, to keep them from straying too far from home. The fear of accidents like the one that befell the chap gathering watercress. The fear that every young woman experiences growing up learning about crimes against women and girls. The fear we have for the unknown, the unexplained and incomprehensible. The fear these boundaries of water, ditches, commons and copses, these wild places hold in our imaginations. Because the details of the ghost story are scant, and the details of any Biggleswade based murder there are untraceable. But the story is a heady mix of social fears and anxieties that we place on the borders of our minds and around where we live.

So, I think murder bridge is one of those tales long twisted into something different from it’s origin and maybe we will never know the truth of it. I chose in my fictional story at the start of the show, a heron leading to the fear of a ghost because just last month I was startled by our local heron one night. It was about 8:30 in the evening and I was walking along the path next to the main road past a local school and playing field. I heard a noise like a bark, and I stopped thinking it was a fox. I looked around for where the noise was coming from and the next thing, I knew a grey shadow rose in front of me. It’s skinny legs dangling as its large wide wings spread and it flew low over my head still making the most unusual sound. I played back a heron warning call on the internet when I got in and realised it sounded just like the noise the heron made. What the heron was doing away from the fields, stream and ponds over the other side of the main road where it usually lives I don’t know, Either way I spooked it and it certainly spooked me!

Thomas Dun

The tale of the Murder Bridge is supposedly only 80 years old. My next tale is far older at 800 years old. In the last episode I told you the story of Black Tom the phantom highwayman of Bedford. He now haunts a roundabout and his ghost has been seen as recently as the 1990s staggering about, head lolling to one side with the appearance of a man recently hanged. Legend has it he was a famous highwayman of the more gallant kind. But the mystery deepened when I investigated because, no trace of a highwayman meeting his name, description or circumstances seems to exist. And then there was the fact that on many occasions Black Tom’s shambling phantom has been seen with another, more shadowy companion. It was this companion I wanted to find out more about.

I first read the theory that maybe Black Tom was in fact based on two Tom’s associated with crime in the area, on the Odell village newsletter for May 2010. Where an article argued that Thomas Dun could be a contender for the legend of Black Tom and the companion ghost.

Thomas Dun’s story is a dark one. And another tale swathed in the mists of time, in rumour, conjecture, mistaken identity and misunderstandings. But picking my way through all of that here is what I know about Thomas Dun.

He was probably an outlaw in the time of either Henry I 12th century or Henry III 13th century. I’m going with Henry III as his reign was long and so there is statistically more time to fit Thomas Dun into his reign.

Thomas’ story appears to first be written down in detail in the 18th century so at least 500 years after he lived. However there appears to have been earlier stories and folklore associated with him which are brought together in the 18th century retellings. Much of his story is similar to other tales of outlaws and robbers, and some of it reads like a fairytale.

The main version of his tale that I have used for this episode is from the book The Lives and Exploits of English Highwaymen, pirates and robbers published in 1883 but is based on the earlier 1724 work of Captain Charles Johnson.

As a child it is said that Thomas Dun was jealous of others, coveting their possessions and lying as easily as others smiled.

Thomas was from or at least settled in Bedfordshire, he certainly terrorised the locality with his robbing and violence. There are many stories which illustrate his brutality where after holding up victims on the road at knife point, and being given their goods, he decides to stab and kill them anyway. Just because he can. He burgled houses and was indiscriminate in his violence attacking both men, women, and children.

He is also portrayed as a master of disguise. He would dress himself in rags and even give himself the appearance of a person with leprosy or some other impairment. But Dun wasn’t content to just beg for pennies in the guise of a disabled man. No, unwary and charitable people would approach him, fooled by his outward demeanour, only for Dun to leap up and slash their throats, grabbing their possessions and fleeing. I find this aspect of his story particularly interesting as it plays into a fear and anxiety that society is still grappling with today. A fear about being fooled or conned by those who appear to be in need or who are faking disability.

This aspect of the story is like a thirteenth century version of the 21st Century “Saints and Scroungers” genre of TV programmes and articles. My previous work in the UK jobcentres and then as a disability campaigner means I know that instances of disability fraud are extremely low. It’s a rare form of fraud. Yet it’s an issue which is so emotive and distracting it’s often used politically to avoid discussions on more complex and prevalent issues And it’s used by daytime TV schedulers as entertainment. And as a disabled person, I have very uncomfortable feelings about why stories like this are still so disproportionately popular. But that’s for another podcast on another day.

Here in the 13th century and the 18th and 19th century retellings I think this story of disguise is included as a warning to travellers to be wary, to be careful who they trust on the road, that things are not always as they seem. But also to demonstrate just how heinous and evil Thomas Dun, was that he would pretend to be someone deemed as the weakest and lowest in society, the shunned and pitied as a way to get rich and satisfy his sadistic desires. (Which opens up another can of worms about how these tales portray disability.)

Yet alongside these stories of violence there are stranger tales as well like these next two stories about Dun that I’m going to tell you.

Although Dun is no Robin Hood, he does have a rivalry with the Sherif of Bedford and takes particular delight in outwitting him. In one story Thomas Dun has brought a gang of likeminded outlaws around him and they capture, kill and rob a group of the Sherif of Bedford’s men, who had been sent to capture them. Yet not content with just evading capture. Thomas Dun and his gang dress in the clothes of the slain Sherif’s men and rampage around Bedfordshire, robbing and looting. The word gets out that the Sherif of Bedford’s men have gone rogue. In an age before the printing press let alone photography, it’s not hard to see why if you were dressed in the uniform of the Sheriff others assumed you were one of his men. It is only when the bodies of the murdered sherif’s men are found and identified that the people of Bedfordshire realise that they have all been fooled as well as swindled and robbed.

I wonder if this story has a hint of the “what happens if the powers that be are in fact the criminals?” Whether it’s politicians, gentry or the law enforcers, how do we know they’re not just a bunch of rogues in disguise? Another allegory that seems pertinent today!

The next story included about Thomas Dun is an even stranger one. It stands out as unlike any of the other tales about him.

The diamond ring

At the time our story is set Thomas Dun had shunned his gang, who he had grown bored of and was wandering the roads of Bedfordshire alone. He had lately robbed a knight of some 400 marks. Yet he could not find a place to spend his money and the night. The rain was lashing down and in the dark tempest he’d lost his way, distracted by dreams of a hot meal, good liquor and a warm bed. Wandering off from the main road he found himself in a wood. Cursing the weather, the poor road conditions, the dripping dark trees and everything but his own carelessness he stumbled on bedraggled and angry. Eventually he emerged from the wood to see a house standing alone in a field, it’s lights blazing against the dark.

He rushed through the mud of the field and the muck of the farmyard to the house. He hammered on the door bellowing.

“Let me in! Let me in!”

Eventually the door was opened, he was admitted and he waited dripping on to the stone floor as the master of the house was sought. Dun could hear the laughter and conversation of many people from a room somewhere within the large house.

Finally, the gentleman of the house emerged, wiping his beard with the back of his hand.

“Not a night to be travelling!” he boomed “Come warm yourself by the fire for a spell.”

Dun did not budge instead he replied sourly

“I need shelter for the night.”

The jovial gentleman thought for a moment

“And I would gladly give it if we had room to spare, but it is my daughter’s wedding tomorrow and every habitable room in this house is taken with family and friends, ready for the celebrations tomorrow. But by all means come and warm yourself and have some food.”

“What of your uninhabitable rooms?” Dun spat. “I must stay the night I will not walk further and I will not be denied!”

The jovial man ran his hand over his whiskery chin looking Dun up and down.

“Well, there is one room that is empty. It is perfectly sound, dry, and warm but no one will set foot in it on account of it being haunted.”

“What nonsense, I do not believe in ghosts and goblins. I will stay in that room.”

The jovial host then provided Thomas Dun with a rich hearty supper, a seat by the fire, and fine wine reserved for the wedding. Dun did not utter a single word of thanks and he ignored the family and wedding guests. Apart from the bride to be, a young pretty woman with chestnut hair, who seemed to be the only person in the room in more of a sour mood than he was. He kept his beady eye on her as he slurped his wine and stuffed his face with chicken legs throwing the bones over his shoulder to crack and hiss in the fire.

He then demanded to be shown to bed. He found the room, plain and simple. Small but sound and not being a superstitious man, he was soon in bed and snoring. Until sometime later he awoke with a start, he was aware that the door to his room was slowly being opened. He assumed it was one of the family playing a prank on him, and he reached for his knife which he always slept with, ready to brandish and use if the mood took him. But as he looked through the corner of his eye, he saw it was the bride to be. She was walking steadily, looking straight ahead. A stray chestnut curl, lying against her cheek. He could not tell if she was awake or sleeping. To his surprise she then pulled back the covers of his bed and lay down next to him. Still staring straight ahead looking up on to the ceiling and saying not a word. He could feel her warmth, hear her breath; she was not an apparition. If she was asleep and he woke her, and she screamed, there’d be hell to pay. And he wanted to sleep and be gone from this place as soon as he could in the morning. So, he lay still.

But no sooner had she lain down next to him, she sat back up and removed from her finger a large diamond ring, which she laid gently on the pillow next to Dun. Then as stealthily as she had entered the room she left closing the door softly behind her. Leaving behind the faint scent of violets and roses.

Thomas Dun could not believe his luck, this young lass had just left him the hugest diamond ring he had ever seen. He quickly pocketed it along with his knife and decided to leave as soon as the cock crowed in the morning.

He dosed back off to sleep only to dream of the young bride to be, who now sat next to him on the bed. She said she did not care for her intended and that if Thomas Dun would take her away from the house that morning, she would give him more gold and jewels than he could imagine.

Dun woke with a start. It had been a dream surely, yet he could feel a warmth next to him on the bed, and that scent of violets and roses was heady in the room. Had it been a dream?

It was early still, the cock had still not crowed, but he felt that he was in a trap of some kind. And with the ring safely stowed away he snuck out of the house without a thankyou or further thought about the young woman and her offer.

As I mentioned earlier, it is a very strange story to be stuck amongst the tales of murder, plundering and cunning disguises. It’s like a fairy tale pops up out of nowhere and then after this interlude we’re back to more tales of Dun committing terrible violence.

I think the Victorian’s may have sanitised this story, as they often did. They were content to portray wickedness of the purely violent kind, but not anything sexual. Yet clearly, we have a young woman in this story, getting into bed with this awful man, but nothing happens between them other than her offering up a valuable piece of jewellery. Is it symbolic, is she offering him something else too?

But Dun is a thoroughly disreputable man, who will not help this young woman even with the offer of a reward. And I wonder if there’s a hint at this being a bargain, he knew would not end well for him. He is in a room with reported supernatural properties, is this woman really the bride to be, or some fairy creature in disguise? Such a promise of more wealth comes at a price Dun is not prepared to take, for risk of it being a trick.

We don’t find out what happened to the bride as the story then moves on to Dun’s last violent deeds and his eventual capture and punishment.

His capture story has similarities to that of Black Tom’s in that the river Ouse is involved. But before we get to that the attempt to apprehend Thomas Dun is tied up with the name of one Bedfordshire town, that of Dunstable.

Dunstable

The folklore of the town is that its name came about after the King of England set up a garrison of men at its site, to capture Thomas Dun and his gang. The Dun in Dunstable is for Thomas Dun. Other versions of this story state that the King attempted to lure Thomas Dun out of hiding by stapling a ring to a post where Dunstable now stands, and Dun fell for the bait.

However it seems more likely that Dunstable is either named after an Anglo Saxon, Duna and means the boundary of Duna’s land. Or it’s from the Old English word Dun for hill and Staple for marketplace, so the market on the hill.

But the story of the King using Dunstable as a place of operation in his attempt to capture Thomas Dun remains a popular folk tale to this day.

Capture

The story of Dun’s eventual capture is a dramatic one. First, he is tracked down to a small village where he is lying low. On being discovered he takes flight on a horse pursued by at first 50 men, this number soon increases to 150 men as word gets out about the pursuit. They gallop across the countryside of Bedfordshire and on at least one occasion, Thomas is dismounted but manages to scramble back up on to his horse and rides on as the crowd of pursuers grows behind him.

After many miles his horse collapses and Dun continues his getaway on foot, the crowds chasing him have now swelled to over 300 people armed with clubs, pitchforks, spades, rakes and other “rustic weapons.”

Thomas Dun exhausted rests for a short while but realises the crowd are almost upon him, he strips off, places his sword between his teeth and leaps into a nearby river to swim to safety. Except the banks of the river are surrounded on both sides. Dun makes it to an island in the middle of the water where he hopes he can lie low. But boatmen are pursuing him, so back into the water he jumps, sword between his teeth and he swims some more but the boat men, catch up with him, beating him with their oars until he is overcome and dragged into a boat and back to land.

Dun is taken to Bedford Gaol where the authorities are good enough to treat his wounds and let them heal for a fortnight before taking him to execution with no trial.

On the day of his execution there is a huge crowd in Bedford to witness it. Dun is led to the scaffold (though it was probably a large tree) and there are two hangmen because he is such a dangerous prisoner. Dun calls to the men.

“I warn you, do not approach me. Or you will pay.”

The hangmen approach him and nine times Thomas Dun throws them to the ground. But on the tenth attempt they subdue him long enough to fix the rope around his neck and he is hanged until he is dead.

Though that is not the end of his punishment. His wickedness was so well known, so many around Bedfordshire had been terrorised by him. And members of his gang were still on the run. So, as a warning and a testament to his crimes. His body was chopped up into pieces. His head was severed from his body and then his head was burnt to ashes. And each town and village in Bedfordshire was sent a piece of his body to be displayed for all to see. I wonder which part Biggleswade was sent? His knee maybe?

It’s a horribly gruesome punishment for a man who committed horribly gruesome crimes.

But does knowing his story get us any closer to knowing if he is the shadowy phantom who accompanies Black Tom’s ghost in Bedford?

Mystery

We’ll never know but the author of the Odell Newsletter speculates that Thomas Dun may well have been known as Black Tom, because in the parlance of the past, his deeds were so evil they’d be known as black deeds. But I’ve not found any evidence that Dun was known by such a nick name. Though Dun does mean grey or dark brown. I could see by having a shade of colour as a name might lead to a play on words.

Some of Thomas Dun’s story has similarities to Black Tom’s own. They’re both held at Bedford Gaol, they both are a particular enemy of the sherif of Bedford, they are both notorious outlaws with something of the mysterious and flamboyant about them, they both attempt an escape in the river.

But Black Tom is a figure that at least some of the town’s folk admired and he is portrayed as a criminal but one of a more gallant nature. Only resorting to violence in defence or if he did not get what he wanted. Many did not want to see Black Tom hanged. His ghost is restless because he felt he had been treated unfairly when the people’s appeal for leniency was destroyed and ignored.

Thomas Dun was feared and hated by the population. He was a man sadistic and cruel in his criminality. It seems all rejoiced at his death. If Thomas Dun’s spirit is restless it is due to his evil nature and possibly the nature of his execution. Later in the episode when I’m talking with Wayne from Eerie Edinburgh we’ll look at another case of an execution that included a mutilation and whether such mutilations have an impact on the associated ghost story.

It could be the case that Thomas Dun and the story of another more recent highwayman have twisted together to form what is now remembered of the Black Tom story. Maybe the illusive sighting of an additional shadowy ghost is an indication of this. Are there two restless spirits? Or two stories being half remembered and attributed to the site or is it a bit of both?

Thomas Dun the pirate

But before we leave Thomas Dun, there is another aspect to his story that leads us nicely into my discussion with Wayne from Eerie Edinburgh.

When I was researching Black Tom I came across another Thomas Dun. This Thomas Dun I think has become entangled with our Bedfordshire outlaw and confusion and mistaken identity has led to all kinds of trouble.

You see there was a man who the English chroniclers called Thomas Dun alive in the early 14th century who was a pirate. In 1315 this Thomas Dun seized an English ship sailing into Hollyhead on Anglesea and looted it. Thomas Dun did this on behalf of Robert the Bruce King of Scotland. Because this Thomas Dun was Scottish. His actual name was Tavish Dubn. Thavish being the Scottish variant of Thomas and Dubn being gaelic for black. So, he was a Thomas Black a black Tom and often referred to as Black Tavish. It is most likely that an English mistranslation of the gaelic dubn saddled him with the name Dun. But as his real name was Tavish and to reduce confusion that’s what I’ll call him from now on. Black Tavish the Scottish pirate.

Irish, Scots and English sources all mention him and how he was a scourge on the Irish Sea. After Bannockburn Robert the Bruce, sent his younger brother to Ireland to fight the English there. Black Tavish assisted in this endeavour by ferrying the Scottish army across the Irish Sea, as well as looting and plundering English supply ships.

Tavish seems to share some characteristics with the Thomas Dun of Bedfordshire, in that it was feared and disliked, even by his fellow Scots. One described him as a “scumer of the se” or scum of the sea.

Black Tavish’s fleet of Scottish privateers proved so good at capturing English vessels, and looting them, that Edward II King of England ordered a special ship to be built to assist in the capture of Black Tavish. And eventually he was defeated by the English Navy off the coast of Northern Ireland. It is said that Black Tavish died on his boat and is buried on one of the skerries, a string of islands off the east strand in Portrush Northern Ireland. A blog entry by Tim Hodgkinson identifies

“The islet furthest east is called Island Dubh. It is probable that it is named after Tavish Dubh, a pirate, who once frequented the Skerries.”

And Portrush has taken Black Tavish the pirate to their hearts holding a pirate festival in his honour. There are even tales that he was buried along with treasure looted from the English fleet on the Isle of Dubn.

So we find ourselves in a bit of an historical pickle. There is a Thomas Dun of Bedfordhsire, villain and highway robber, who may or may not have given his name to Dunstable and may have lived in the 12th or the 13th century.

We then have a Tavish Dubn which when anglicised is Thomas Black, But was mistranslated as Thomas Dun but who was also known as Black Tavish or black Tom, who was a Scottish pirate in the early 14th century.

They’re not the same man clearly. But it is conceivable why they got mixed up and confused in the 18th century when the first books about pirates and highwaymen were proving popular.

But certainly, by the time of the source material I was using for Thomas Dun was printed in 1883 Thomas Dun of Bedfordshire was not being confused with the pirate.

However, the internet seems to have re-entangled these characters again somewhat.

I think it is safe to say though, that the Black Tom or Toms who haunt that Bedford roundabout are not Black Tavish the Scotish pirate who I doubt ever set foot in Bedford.

That’s not to say that there aren’t real links and themes within these stories of ghostly criminals or ancient outlaws between Bedfordshire and Scotland.

Across the whole of the UK and Ireland, Europe and the world there seems to be a link between crimes and ghost stories. So many hauntings seem to have a connection to a crime or a victim of crime or the criminal themselves and I really want to understand why.

So I decided to have a chat with Wayne from the Eerie Edinburgh podcast and YouTube channel. As he admits to me in the interview you’re about to hear, he just loves ghost stories. He really does. And Edinburgh is a city I know well, and I’m fascinated by it. My husband is from nearby over the Forth in Fife and has lived in Edinburgh as a student. It’s a city with a dark history and its ghost stories reflect that, many centring around crime and criminals. And Wayne’s brilliant podcast Eerie Edinburgh tells the less well known ghost stories of the city and it’s surrounds. Always infused with history and a real sense of Scotland’s majestic scenery and past I can not recommend enough that you give Eerie Edinburgh a listen or a watch on YouTube. But here’s the interview and apologies that I was full of cold and Wayne was recovering from one when we recorded this!

Interview with Wayne from Eerie Edinburgh

Nat: Thank you so much Wayne for agreeing to join me today to talk about criminal ghosts and the victims of crime who haunt places. But before we get on to that, can you just tell us a little bit about yourself and your wonderful podcast? Eerie, Edinburgh.

Wayne: Thank you. Now thanks for that. It’s an honour to be asked on. I really appreciate you giving me the opportunity to speak to you about ghost stories. So Eerie Edinburgh started during lockdown. Really well, it started when I was a kid. I’ve always been fascinated with ghost stories. I could listen to people talk about ghosts for days on end. It’s one of these things that throughout my life I’ve come to the conclusion that there’s only a few things that genuinely interests me and one of them is ghosts. Whenever somebody talks about ghosts, I’m all ears and I’ll just listen and listen. And I love it. And I love the story aspect of it. Like when Most Haunted and things like that were really popular, it wasn’t really the investigation that I liked. I liked the history and I liked the storytelling part of it. The introduction to them. So I’ve always had a passion for it.

My sister used to torment me with ghost stories and things like that. So. It’s always been a strange obsession that I’ve had and during lockdown, I kind of read a lot more. I started to read up a lot more on the stories from Edinburgh and what I kept coming across, all you hear about were the stories from the vaults and stories from Greyfryers and having grown up in Edinburgh, I know that there are a hell of a lot more stories to tell than them. So I genuinely was kind of a bit concerned that we’re gonna lose all of these amazing, wonderful stories from the city and it’s just gonna be, it’ll just become Greyfriars and the vaults.

So I thought, I was bored. I needed a wee bit of a hobby. Like everybody. I didn’t want to go to baking banana bread or anything like that. I had experience of running a website in the past. I quite like hill walking, so I used to run a hill walking website about 15 Years ago, so I thought I’ll give that a bash and created the Eerie Edinburgh website and started to write up some of the stories that I was familiar with. Then I kind of thought there’s more to it than this and it’s when I joined Twitter with the Eerie Edinburgh site and I discovered the Uncanny podcast and the uncanny community, who were just this bunch of people that talked about ghosts, were really passionate about it, really inclusive and just kind of took me under their wings. It felt like, I hate to use the term safe space, but it felt like a safe space to talk about ghosts. And seeing some of the the things that people were creating, the podcasts and the stories. In particular, there’s a guy called John Tantalon who runs North Edinburgh Nightmares. I came across his YouTube site and he focused at that time more on the Edinburgh stories centred around Leith, which is where I live. And I thought he’s a wonderful storyteller and I just kind of thought, let’s give it a wee crack on YouTube.

So I started with a wee story about a murder. It’s called a murder in Bible Land which was about a murder that happened in the Canongate area of the Royal Mile. And the ghost of a young woman wearing her tartan dress was seen. Quite regularly it’s just a short, wee video. It ended up getting about 5 views after a week, which I was delighted with because I thought that I would be the only person that would watch it. So encouraged by that, I then worked on another video called Hunting in Buckingham Terrace and after about a week with that, it had about 9 views and then I went to sleep and woke up and it had 1000 views. And then it just skyrocketed. And I went from having a couple of subscribers, one of which was me, to having over 100 and it just kept building and building. And now it’s about 9000. Subscribers I’ve put about 35 videos out, and it’s had over eight million impressions, which just completely blows my mind.

Nat: It’s amazing. It’s such a great story. There were so many things then that I wanted to respond to: the love of ghosts completely I can relate to that. I was the big sister, terrifying my little brother with ghost stories growing up. And again the uncanny community, we wouldn’t have Weird in the Wade if it wasn’t for uncanny and the uncanny community.

Wayne Yeah, I remember watching the video event that you were at and talking about the haunted pound stretcher. So I remember seeing that it was a really interesting story.

Nat: Ohh so were you one of the remote viewers? That’s not the word is it? Remote viewer that’s something they do in psychic research. [laughs] You were one of the zoom or the online viewers on the day at Uncanny Con?

Wayne: I was, yeah.

Nat: Ohh, fantastic. It was great. It was a great show.

Wayne: It was, yeah, it was really enjoyable. Really nice to see so many people just feeling like they could talk about their experiences like that. It was great.

Nat: Thank you so much for telling everybody then about Eerie Edinburgh. It’s a fantastic podcast. You don’t just cover Edinburgh, you do cover wider Scotland as well. And I have a particular love of Edinburgh. My husband’s from Fife. He lived in Edinburgh. We spend a lot of time in Edinburgh. But one of the things that I’ve noticed about Erie, Edinburgh your podcast, but also just the ghost stories in general in Scotland, is that many of them are centred around either crimes or criminals and in fact I think that goes across the board that there’s loads of ghost stories. That are about shocking crimes. The criminals that do those crimes and also the victims of the crime. And I wondered if you’d come across any that really particularly stick out in your mind in, in doing it at Eerie Edinburgh that are ghost stories that kind of relate to criminals or victims of crime.

Wayne: Yeah, there’s like you said, you know, Edinburgh’s got a very murky past. There’s been a lot of intrigue, a lot of murder. You know, if you think back to some of the historical figures throughout time, probably a couple of names that that stand out are the resurrectionists Burke and Hare, are synonymous with darkness and things like that. So there are so many stories where. Like you say, there’s the ghost is the victim. You know they’ve been murdered. Or they were the murderer.

Some of the ones that that spring to mind, one of the first stories that covered was the White lady of Corstorphine. It was a separate village to the West of Edinburgh. That was amalgamated into the city 150 years ago or something like that. It’s kind of still got its own character to it. And in in Corstorphine it’s an area that there used to be a castle, Christophine Castle, Christophine Castle no longer stands, but there is a ducat or a dovecot that stands. That was part of the castle and the castle was owned by a laird at the time that the this happened. Laird Jamie Forrester. I believe his name was. And he was a notorious womaniser and drinker. And he struck up a relationship with a woman called Christian Nimmo, who was already married and they carried out an illicit affair for quite a while. And the place that they would meet would be that ducat. And Christian Nimmo, she was known as having quite a fiery temper. And on one occasion, because of the Laird’s drinking habits, he turned up late and she was particularly angered by this. And he was quite belligerent with her. By all accounts. The story was relayed by Christian’s servant that used to accompany her. So they argued. And she drew the Laird’s sword and stabbed him through the heart with it.

She tried to escape, but she was chased down by the Laird’s sons, who eventually caught up with her. She was tried at the toll booth in Edinburgh, and she was executed for murder. Obviously, but ever since then, her ghost has been seen on quite a regular occurrence. Up until maybe I think there was a storm and around about 2000 there was a huge Sycamore tree that used to stand next to the Ducat and they the sightings offer start to wane after the storm when the Sycamore tree was blown down. It seems to have been linked to the Ghost that was seen there, but she was often seen wandering around the ducat, as if waiting for him, but interestingly, she was seen carrying the sword that she stabbed them to death with in her hands.

So it’s quite a well known story, a couple of friends who live out in Corstorphine, none of them I’ve seen her directly themselves, but it was an accepted story that that was a haunted ducat. Other people had seen something or felt something in that area. That’s your kind of classic white lady ghost story, which I think everybody who likes a ghost story loves a white lady or lady in white.

Yeah, another one that is possibly it’s not really thought of as a ghost story, but it’s a very famous story. As Deacon Brody, I don’t know. Are you aware of Deacon Brodie’s name? Ring a bell?

Nat: I love this story. I love Deacon Brody for a couple of reasons. Have you been to the writers Museum?

Wayne: I have. I love that building.

Nat: Yeah. So I really love Robert Louis Stevenson and he owned Deacon Brodies cabinet. One of the cabinets he’d made. And you can see it in the museum. So, it’s one of the reasons I love going there. So yes, tell us about Deacon Brody.

Wayne: So for people who don’t know Deacon Brody, the paradox of Brody’s life inspired Stephenson to write the strange case of Doctor Jekyll and Hyde. Brody by day was a respected figure. He was a locksmith and also head of the town council. But by night he was a thief.

He was another man who had a drinking habit. He had a few mistresses by all accounts, so he needed the money to accommodate that lifestyle, being a locksmith. When he was asked to create a lock, if it was somebody who was quite well off, he’d make a copy of the key and after a few weeks, once he felt suspicion wouldn’t have turned on him. He and a group of people would break in and rob the houses he was quite a successful guy. He got away with this for quite a while and the reason he was caught was when they’d planned a raid on the Excise office in a place called Chesley’s Court, which is just off the Royal Mile.

Chesley’s court, interestingly enough, is another haunted location on the Royal Mile. That’s haunted by a lady in black. She’s often heard, there’s one property where I, I believe I’ll try to refresh my memory. It’s kind of 18th century. It was a woman who lived on her own. And she would hear somebody come up to her door and knock on her door, what we’d call an Edinburgh chap door run. But every time she opened the door, there was nobody there and she would have sight down the stairs and at night it would happen and there would be nobody there. There’d be no footsteps of people running away. Her brother ended up coming to stay. And if memory serves, he saw the lady in black. Down at the side of his room. I didn’t. John Taranto from north Edinburgh nightmares. He’s had some experiences himself there.

So yeah, that’s another hundred area, but back to Deacon Brody. They’ve broken into the Excise office, but one of the staff had returned. This was about 8:00 at night and they returned and had interrupted them. So he had to flee. He was, he was recognised. So he had to leave Edinburgh. He tried all sorts to get away. He travelled from Leith and fled to Amsterdam to avoid capture. He was eventually caught, and he was another one who was hung. I think he was hung in the front of about 40,000 people. It’s quite a hell of a crowd considered in Edinburgh. I think it was about 60,000 people at that time.

Nat: Yeah, that’s nearly everyone, isn’t it? Turned up.

Wayne: Yeah. Well, if you think about Edinburgh in the olden days, the Old Town before the new town was built, the Royal Mile. That was what Edinburgh consisted of. So it’s 60,000 people living in. It’s like a square mile? Yeah, not a large area at all. That’s why we have the tenements, the world’s first skyscrapers. But yeah, to the point that he died he was a chancer, he tried his best to get away with it. He tried to bribe, or I think he did bribe the hangman to ignore a steel collar that he had constructed and he’d insert a silver pipe to help support his neck so that his neck couldn’t break on the fall. Apparently, it didn’t work or it may have worked, depending on the story that you believe. Some people think he got away with it and escaped. But the he’s apparently buried near Bristol Square, there’s an old church with a cemetery there.

His ghost was seen apparently, He roams up and down the Royal Mile, holding a Lantern with visible sores around his neck from the like rope marks from the burn marks from the rope that was used to hang him. It’s not a famous story. The story that’s more associated with him is just his life and the Jekyll and Hyde aspect to him. But there are reported hauntings. Of Deacon Brodie marching up and down the Royal Mile. Very angry about the fate that he succumbed to.

Nat: Yeah, what’s really interesting, right, is that in a way, this links to the story that we told in the last Weird in the Wade episode about Black Tom in Bedford. That one of the reasons he’s seen as a ghost is that he feels he shouldn’t have been hanged. He. But you know, the story goes that he was given a petition or that the judge should have been given a petition saying that, you know, the people of Bedford did not want to see him hanged, but he was hanged anyway. And it’s partly why he can’t rest. And I think that leads on to that question that I wondered if you had an opinion of Wayne, which is why do you think so many ghost stories centre around crimes or or criminals? In the case of say Deacon Brodie or Black Tom, it’s that idea that they feel that they were treated unjustly in some way and shouldn’t have been hanged, but it’s far more complex than that I think, isn’t it?

Wayne: Yeah, and it’s a good question. I think what you’ve said there that it’s unfinished business is possibly an explanation for it. You know if you believe in that a ghost is a spirit of a deceased person, that that can’t find rest. Then unjust actions are gonna make that you know what am I trying to say here? What am I trying to say, Nat?

Nat: You now I think, I think I know what you’re trying to say. That idea if you subscribe to the sort of Christian or in fact quite a lot of religious beliefs that there is a life after death and that we should move on to somewhere else, whether that’s a type of heaven. Or a type of hell or a reincarnation, but that there is something else. And that actually somehow that cycle gets broken and you can’t move on to whatever’s next because you feel – like you said there’s unfinished business. That also explains, even if you don’t necessarily believe in ghosts, it explains why the people who tell the stories might believe this because they believe in that idea of heaven and hell or something after death and so believed that there could be times when that natural cycle gets disrupted.

Wayne: You said it far better than I could say it. Yes, how you’ve described it as exactly what’s in my head. I just can’t get the words to work. There is a story. There’s a chap that’s known now as Johnny, one arm who was a guy called John Chesley. In life he was a 17th century businessman. He was married. He was another drunk who mistreated his wife. She managed to successfully sue him for divorce. He lost the case despite his protestations, and the judge completely sided with his wife and awarded her maintenance that in in today’s money, would be about £80,000 per year, so he was irate. Because of this, you know he was in the in court, he was threatening the judge. You know “this won’t be the last you’ll see of me” kind of thing. And it wasn’t, and the judge tried to put what happened out his mind he had gone to a service I think it was in St. Giles on the Royal Mile had left, he left with a couple of friends and he felt like he was being followed and it turns out he was being followed. Chesley had waited until the judge had gone down one of the closes and was on his own before he shot and murdered him. He felt so just in his actions because he felt he’d been so wronged by the judge’s decision. He didn’t try and flee. He just stayed there and waited for the police to come. Take him. He was executed.

The reason he’s now called Johnny one arm is because they cut off the hand that he used to pull the trigger and they hung it around his neck as he was being executed. And they also hung the pistol round his neck that he. Used to shoot the judge. And he’s another one who’s seen in the area of the assassination. But he’s also seen where he used to live, which is an area of Edinburgh, to the again to the West and more to the SW called Delray, which is where he used to live. And I get he’s another angry ghost that’s unhappy and seems like he’s got unfinished business as, as you said. But again, it leads into what you said that he feels this unjust and he felt he was injusticed in life. What happened to him in life he carries that on into death.

Nat: Yeah, that’s such a fascinating story and has links to the story that I’m telling in this episode in a way, about this idea of being mutilated as well as executed in the past. The character that I’m going to look at, which is Thomas Dun. Execution, it wasn’t enough. He was seen as so evil. It wasn’t enough to just execute him. He also was then sort of chopped up and bits of him were sent to different parts of Bedfordshire. And again, it’s kind of that seems to be one of the reason why people think he cannot rest because it wasn’t just a normal execution. He was actually sort of, you know, defiled in a way that was seen to be extreme. If you see what I mean. Although he was an extremely, extreme criminal as well.

Wayne that has just been fantastic listening to those stories, I wish we had more time, so I may if you would be up for it and invite you to come back on a on another episode so we can have a talk about maybe a different type of ghost story. If you would be interested in doing that?

Wayne: I would love to. This has been a lot of fun yeah, absolutely.

Nat: Ohh, that’s fantastic.

End

Again I’d like to thank Wayne from Eerie Edinburgh for joining me today to talk about ghosts with a connection to crime. You can find Eerie Edinburgh on YouTube and other podcasting sites. I’ve put links in the show description and on the blog where there’s a transcript and notes for this episode including the discussion with Wayne.

I think what this episode has highlighted for me is that sometimes crimes are so shocking, and spread so much fear in the communities where they happen that ghost stories emerge as a way of preserving that fear or the fear its self transforms with time into something different. Like with the Murder Bridge.

Other times the deeds of the criminal are just so shocking and the manner of their deaths and executions are equally ghoulish and this leads to their memory living on far longer than accurate information does about their crimes. They become the bogey men to scare children with. Yet another reason not to commit crime, you’ll end up like Thomas Dun hacked to pieces and unable to even descend to hell. Doomed to wander with a twisted neck and purple face for eternity, tormented and broken.

And unfinished business is another reason for hauntings, where victims of crimes and criminals feel that there is more that they needed to do in life so they can’t rest either.

In the next episode we’ll look at these phenomena in more detail. Where a victim of crime is said to haunt Green Park in London because he can not move on from the sorrow caused him by the theft of his beloved violin.

We’ll also look at where a real-life crime, becomes so notorious all details of it are swollen out of proportion over time. Until any strange phenomena is blamed on it. We’ll be exploring the body snatchers of Biggleswade and yes returning to the tunnels!

This next episode should be out within the next three weeks so earlier than usual, because at the end of March or right at the beginning of April, the first Weird Wanders episode is due out! More about that next time!

Thank you so much for listening today, I appreciate your company so much. Remember if you want to get in touch with me then you can email weirdinthewade@gmail.com. Social media links are in the show description.

Weird in the Wade is researched, written, presented, and edited by me Nat Doig

Theme music by Tess Savigear

All additional music and sound effects by Epidemic Sound