Show Notes and Sources

Bedford Ghost stories including Black Tom

Here is some recommended reading for Black Tom and other Bedfordshire ghost stories.

Bedfordshire Libraries ghost pamphlet: Download the booklet here.

Damien O’Dell’s books about paranormal Bedfordshire are a great source for stories including Black Tom.

William H King Haunted Bedford is another good read.

This newspaper article from 2021 shows that the story is still topical!

The 1941 newspaper article I used is from: Bedfordshire Times and Independent – Friday 06 June 1941

History of the Black Tom area of Bedford

The virtual Library has this to say about Black Tom area of Bedford.

A BBC archive about growing up in Black Tom during World War II.

History of Highwaymen including Dick Turpin and Shock Oliver

This Knights of the Road, is a great programme from the BBC, although it’s not available on the BBC I found a version on YouTube and it’s available on Brit Box.

Bedfordshire Archives have this on local highwaymen.

More information on Dick Turpin can be found here.

Shock Oliver’s story is covered here on a blog about old pubs of Baldock.

Show Transcript

Dramatic Intro

January 1845 on a cold night just north of Bedford. Dr James Walker shrugged on his thick overcoat then reached for his top hat. He’d just paid a visit to a patient, a farmer with a raging fever. He’d done all he could and promised to visit the next day when hopefully the fever should have broken. The farmers wife had insisted on seeing him to the front door, a candle flickering in her trembling hand.

“Now Mrs Harbird, do you need me to go over anything again for you?”

“No Dr, thanking you Dr, I will do just as you say. Sir, are you sure you don’t want old Joe to take you on the cart back into town? It is not a nice walk after dark.”

“It is not a long walk though, Mrs Harbird, and the moon is bright. I shall be home in half an hour.”

“It’s not the dark nor length of the journey doctor, it’s having to pass Black Tom’s Grave that I am afeared for you sir.”

“Oh, Mrs Harbird do not worry. Those stories are just that, stories, and a good thing too as they keep the children away from that open sewer there, which is the only foul thing about Black Tom’s Grave in my reckoning! The sooner the town approves of a proper covered sewage system the better.”

Mrs Harbird didn’t look reassured, but Dr Walker was determined. Old Joe was an ancient boy with weak eyesight, the pair of them would end up in the ditch at Black Tom’s Grave if Old Joe was allowed to drive the rickety cart into town in the dark. No, the walk would do him good.

It was a straight road back to Black Tom’s Grave and into Bedford. There were trees on either side of him, skeletal branches dark against a night sky lit silver by a bitterly bright moon. Black Tom’s Grave was in his thoughts as he walked. There was no grave there that Walker was aware of. It was just local superstition and folklore. The kind of thing his father had a passion for collecting. The local inhabitants claimed that an outlaw of some distant unspecified past, was buried there, his name Black Tom. Everyone called the place Black Tom’s Grave. Walker knew that it had been a custom to bury outlaws and even poor wretches who took their own lives at a crossroads. But Black Tom’s grave wasn’t even a crossroads, but a triangular intersection of three roads and the ditch on one side which was currently being used as a most insanitary open sewer.

He was suddenly weary as he trudged on. He listened to the sounds of the night a distant owl, possibly a snuffling hedgehog. He had the whole lane to himself; he wondered if he’d see another soul before he got home on such a cold night. Walker’s breath flared and frosted in front of him in the moonlight.

Then a little way ahead of him where the road opened out into the triangle of Black Tom’s Grave, Walker saw what he thought was a dark figure cloaked and hunched low to the ground. The moon shined coldly on to the figure but it was somehow indistinct. But to Walker’s eyes there was definitely some poor wretched person hunched there. It wasn’t a place to stop and rest nor spend a night. Not even the most desperate urchin, tramp or vagabond would bed down at Black Tom’s Grave.

Maybe they were sick.

Dr Walker quickened his pace towards the hunched figure ready to provide medical aid if it was needed.

As he drew close, he was about to call out to the figure, see if he could rouse them before he reached them. But instead, he stopped, dead in his tracks.

Walker’s footsteps must have been heard because the figure was moving, their cloak falling behind them as they lurched from a crouched position into standing. They wore no hat on their head because no hat would have stayed in place. Although the figure was now on their feet their head lolled at an impossible angle to their left, as if their neck was clean broken. Their left shoulder was hunched low to accommodate it. The face was dark with bruising, mottled and blotched. Their tongue hung loose from their mouth, longer than a tongue should stretch.

Dr Walker had seen many dead bodies, in his training he had even dissected some, many were the bodies of those poor wretches executed for their crimes. Those hanged. And they all looked like this vision in front of him. There was no way a hanged man could walk or even stagger as this fiend did in front of him.

Yet something in his doctor’s disposition and training meant that Walker could not run in fear. He stepped forward towards the horrific unfortunate creature. Was it theatrics he wondered, or a real injury that mimicked hanging but meant the poor man had survived?

The staggering ghoul seemed unaware of Walker and was shambling in no particular direction. Just lurching around on the spot.

Walker was close enough now that he could see the injured man’s face more clearly, the eyes were bulging, and to Walker’s horror he realised that the flesh of this apparitions face was rotting, not just mottled with bruises but with decay. This thing was not alive, not in any medical sense of the word, Walker was sure.

Now Dr Walker stepped back, tried to think about what to do. Should he call for help or would that alarm this aimless but horrible thing in front of him.

And then he saw to his right, on the edge of Black Tom’s Grave a figure approaching, help he thought shaking with relief.

But the figure that emerged from the shadows into the moonlit triangle of dirt in front of him remained just that, a shadow. Walker could see right through this figure; it was like seeing an outline of a man with no substance to him at all. Both the shambling hanged man and the shadow seemed unaware of Walker, but they appeared to greet each other. Bowing.

Walker’s heart was thumping hard, his ribs ached, he could feel a cold sweat trickling down his back. His head swam and stomach lurched, and Walker doubled over as if to vomit. He wasn’t sick, but a wave of cold disorientation drenched him. He looked up from his bent position to see the creature take one lurching stagger towards the shadow phantom and then they both vanished.

Now Dr Walker was sick. He staggered backwards and sat on the cold ground with a thud. His throat sore, his mouth dry, rancid. Had he just seen Black Tom, the phantom highwayman? What was the shadow figure he had seen at the end? Was he losing his mind?

For many years Dr Walker did not tell a soul of what he saw that night, he became convinced that the noxious fumes from the sewage ditch itself was the cause of his hallucination. He doubled his efforts to have the ditch covered and a decent sewer system built in Beford. In 1849 the town board finally gave permission for the sewer to be built though it was not completed until the 1860s.

Maybe it was the fumes from the sewer that upset Dr Walker that night, but he was not the only person to see two ghostly figures haunting Black Tom’s Grave in the 19th century and beyond. Sightings have been as recent as the 1960s and 1990s when a decent sewage system had long been in place. So, what is haunting Black Tom’s grave?

Welcome

Welcome to Weird in the Wade, I’m Nat Doig and today I am going to tell you the story of Black Tom, infamous highwayman and ghost of Bedford. We’ll investigate what we know about this favourite folklore character of the town as well as learning about other infamous characters whose restless spirits still haunt the very streets they plundered. We’ll explore attitudes towards criminals in the 18th and 19th century as well as today, and ponder if we will ever know who Black Tom truly was.

I had to take a few liberties with the introduction. Dr Walker is an invention of mine, because although it is widely reported that there were sightings of Black Tom in 1840s Bedford, I could find no detailed first-hand accounts. I did find contemporary references to the inhabitants of the New Town areas of Bedford being troubled by a ghost in the 1840s but it was written up in the newspaper as if it was common knowledge and there was no need to go into details. What I did discover about Black Tom’s Grave from that time was that it was frequently mentioned in the local newspaper as a sight of an open sewer. The minutes from town board meetings are reproduced at length as the good and the worthy of Bedford debate what to do with the insanitary conditions. And this got me wondering if there was a link between this health hazard and ghost sightings. I have Doctor Walker wonder if he is hallucinating because of the noxious fumes from the sewage. But that might not be the only explanation.

I am aware of another town in Bedfordshire using the story of ghosts and the fear it created, to encourage improvements to be made to the streets. In 1934 Markyate church in the south of the county had been petitioning for street lighting to be installed along the lane to the chapel. Finally, the vicar complained that parishioners were afraid to come to church for evensong due to a fear of a phantom white lady on a horse haunting the dark path. Lights were soon installed after the haunting was reported and funds were raised. So maybe the ghost stories of the 1840s connected to Black Tom’s Grave were playing a similar role. Possibly keeping children away from the area and adding to the unsavoury nature of the place making it all the more urgent to clean up that ditch!

But the area was known as Black Tom’s Grave long before the open sewer.

Yet, the first account I can find of Black Tom the person rather than the place in print, is from an article in 1941 where a diary column in the Beds Times and Independent covers two folklore characters of the 19th century. Black Tom and Spring Heeled Jack. Writing 100 years after the sightings of Black Tom’s phantom the account given is similar to modern versions of his story and also in some key respects different. But we’ll come on to that later.

Black Tom Town

Not every town can boast an area named after a folklore criminal, but Bedford’s Black Tom district is named after just that. Or is it in fact named after his ghost?

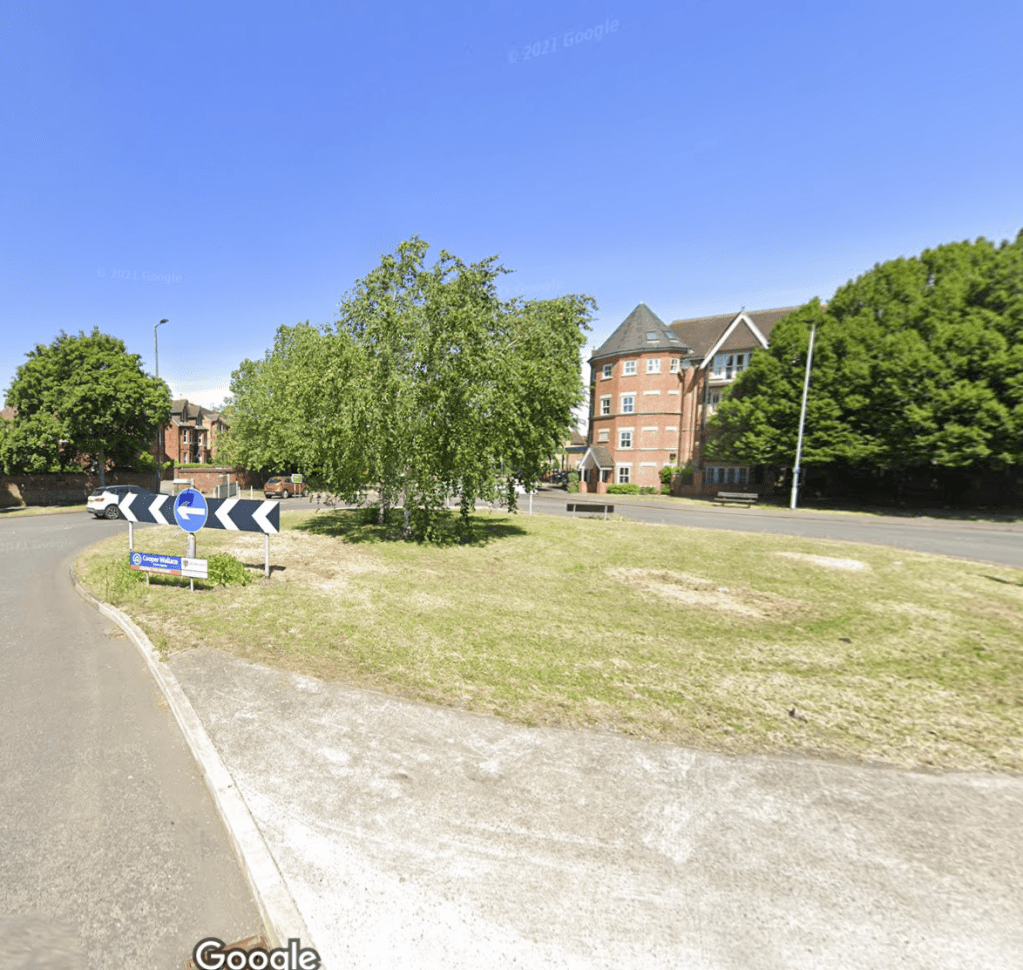

Black Tom is the unofficial name for an area north of the town centre in Harpur Ward. It takes its name from what is now a roundabout but has for many centuries been an important intersection. As I mentioned earlier the area where Union and Tavistock Street, and Clapham Road met has been known as Black Tom’s Grave for some time. And it was this that gave the unofficial name Black Tom to the area. Still today you can find a Black Tom Bakery selling sourdough bread, and pubs boasting the best beer in black tom in that area of Bedford. A housing estate in the area is known as the Black Tom estate, and there is a memoir written about growing up in Black Tom during the second world war.

The legend goes that Black Tom’s Grave is the site of the burial of an outlaw, a highwayman named Black Tom. His grave is in such an unusual place because it was the site of the old gallows. Or because crossroads and junctions were once where criminals were buried hundreds of years ago. Except no one can decide just how long-ago Black Tom lived. The very specific date of 1607 as his birth or death is given by some whilst others say he was active in the 18th and even 19th centuries.

I can not find any documented evidence of a criminal known as Black Tom, of any kind living and or dying in Bedford in the 18th or 19th century. But there were many highwaymen of that time with the name Tom. However, it was unlikely they’d have been hanged and buried at the site of Black Tom’s grave past the mid-18th century. By then hangings were taking place nearer the site of where Bedford Gaol currently is. Prisoners were buried within the gaol or claimed in some cases by their families.

But I have read as many versions of Black Tom’s origin story as I can find, from ghost story compendiums, and newspaper articles spanning the last 80 years and here is my retelling of the tale of Black Tom, his life, death and haunting.

The Tale of Black Tom

Tom was born in Bedford during the 17th century. He came of age just before the civil war broke out, when the country was on edge, simmering with discontent. He was given his nickname because of his shaggy raven black hair, an attribute he was very proud of, and his keen brown eyes and tanned skin. He was a striking figure well known in his neighbourhood especially to the young women, and the young men who liked a drink. He was no puritan and had little sympathy for their parliamentary cause.

Tom was a troubled young man, restless, always on the move; he could never sit still. He didn’t have the patience to learn a trade, nor the constitution for hard work in the fields. He had been a sickly child. He argued with his parents, snapped at his siblings, or led the younger ones astray, taking them drinking. Eventually his parents had enough and demanded he either contribute to the household or move out.

Tom had no intention of moving out of his family’s home, it was warm and comfortable if modest. He needed to find a way to make some money. There had been a lot more travel on the roads lately, as discontent in the country rumbled on. Many errands were being run to and from London to towns north of Bedford. There were many inexperienced and unwary travellers who gave Tom the perfect opportunity he thought. These gullible travellers were crying out to be robbed, he thought. So, Tom set himself up as a footpad. He had no horse; he instead would accost wealthy travellers to and from Bedford on foot. With a gleaming dagger he demanded money and jewels and if a victim put up a fight, or did not comply, Tom thought he was in his rights to cut that man. Though he never set out to kill.

Now Black Tom was no Robin Hood, he did not share out his loot amongst the poor or his friends and family equally, but he was generous with his ill-gotten gains, and protective of those who he cared for. So, amongst the few who knew of his criminal exploits he was tolerated and, in some cases, admired.

But his thievery was not going unnoticed. The Sherif of Bedford was determined to put an end to Tom’s activity and one night the Sherifs men laid a trap for Tom. Posing as two gullible gentlemen travelling from Bedford to Northampton, they ambled noisily along the road hoping Black Tom would strike. Tom took the bait and as he leapt out on the men with the cold metal of his knife gleaming in the moonlight, he was stopped in his tracks when the travellers produced two firearms. Tom was seized and taken to Bedford Gaol, which then was in St Paul’s Square. He was shackled in chains and handled roughly by the gaol keeper.

Black Tom was a cunning man and charming. Within a day he was out of the chains posing as a polite and helpful prisoner to the gaolers. He got a message out of one of his friends, a young woman who that very night came to the gaol and distracted the gaoler with some flirtatious talk and Tom was able to make a daring escape.

Black Tom was now not just a wanted man, but an outlaw on the run, yet he didn’t run far. His neighbours and family accepted him back, hiding him from the authorities. Even those who did not approve of his thievery were in awe of his ability to escape from the gaol and sheriff’s men. No one was fond of the Sherrif.

But this was a time of growing puritanism and some in Bedford were not impressed by Black Tom’s antics and were determined that he would see justice. They were concerned that the people of Bedford were distracted by Black Tom and tales of his exploits, in thrall of him, they wanted Tom caught.

So, it wasn’t long until the Sherrif was sent word of Tom’s whereabouts, and he sent 20 men to apprehend him. Tom was tipped off about their approach and he ran as fast as he could south. He was determined not to be caught again and locked up. Being imprisoned was worse than death. He would rather die than be in chains again. Tom ran but the Sherrif’s men on horseback were faster and so on reaching the river Ouse, Tom leapt into the water. He thought he might make it to the other side, and if he didn’t, he would rather drown than be caught.

But the water of the Ouse was thick with weed and Tom was tangled in it, floundering. He gulped and gasped for air as he struggled to free himself. And then he went under. The Sherrif’s men fished him out of the river, and all thought he was dead as he lay on the riverbank, even the sheriff. But on being rolled over by a kick from one of the sheriff’s men Black Tom suddenly convulsed and spluttered out the water from his lungs and he breathed again.

This only added to his notoriety. Black Tom the outlaw who could not be drowned!

Black Tom was sent to the gaol and was treated very cruelly there by the gaoler and his turn keys who had been humiliated by Tom’s escape. So, when a petition of pardon for Black Tom arrived at the gaol to be passed to the magistrate the next morning. The gaoler instead threw it on the fire. The petition had been made up by the residents of Bedford who did not want to see Tom hanged.

The magistrate never saw the petition for pardon, and because of Tom’s previous escape from gaol it was decided that rather than wait for the assizes and a trial, Black Tom should be hanged as soon as possible. That very day, they marched Tom through the streets of Bedford to the old gallows spot, near the place that now bears Tom’s name. The streets of Bedford were lined with onlookers, many sad to see Black Tom treated so, but others pleased that the law had caught up with this criminal at last.

Passing a group of men drinking wine at one of Tom’s favourite inns, as they waited for the execution, Black Tom hoarsely asked for a bottle of his own. His captors would not allow it, but Tom just laughed calling to the men with the wine “I’ll be back for that drink later then!”

Most of the crowd laughed but the superstitious amongst the townsfolk looked anxious. The outlaw had survived a drowning. Some said he could make himself invisible and that was how he had escaped the law for so long. Others said the devil was his accomplice.

Black Tom was hanged that day, and three separate medical men were found to confirm that he was indeed dead. But the Sheriff, a superstitious man, insisted that Black Tom be buried at the nearest junction and with a stake through his heart. This was the only way to make sure his spirit and his body stayed put in the ground.

The hauntings

It seems that for a century at least Black Tom did rest, or at least his spectre was not sighted. The strange triangular piece of ground between the intersections of Union, Clapham and Tavistock became known locally as Black Tom’s Grave as his notoriety lived on amongst the inhabitants of Bedford. In the mid-19th century as we heard earlier, new families moved to the northern reaches of Bedford, and that is when Tom’s ghost became restless. It was an open secret that Black Tom’s Grave was haunted, and that his ghost was seen as a cloaked and hunched figure at the side of the ditch there. Sometimes there were two shadowy figures glimpsed. The newspapers reported that women were afraid to walk there alone, everyone was afraid to pass by there at night. Children no doubt dared each other to approach the intersection of roads but never actually cross Black Tom’s Grave by themselves.

Just a short walk north of Black Tom’s Grave, along Clapham Road before you reach the river there was a lane known as Cut Throat Lane, an apt name maybe for a place where Black Tom had preyed on travellers. It seems that the Sainsbury’s and Aldi superstores off Clapham Road today stand where Cut Throat Lane once was. Cut throat Lane replaced by cut throat prices as my friend Pete said.

Reports of seeing either Black Tom or his companion phantom subsided as the 19th century wound into the 20th and the town of Bedford grew, soon expanding on all sides around Black Tom’s Grave. That area of town took his name, unofficially. As time wore on many locals who knew the area as Black Tom, forgot or did not know who it was named for.

Until the 1960s when in 1963 a group of people walking along Union Street towards Black Tom’s Grave, all witnessed a figure in dark, old-fashioned clothes staggering towards them. It was broad daylight, there was no mistaking what they saw. His head was lolling to one side, his face purple and blotched. Alarmed the witnesses thought he must have been in some kind of accident, some rushed forward only for the injured man to disappear in front of their eyes. These reports led to the legend of Black Tom being remembered, revived. More people reported seeing shadowy figures at the side of the road near Black Tom’s Grave during the 1960s. Sometimes there were two figures, sometimes just one. But nothing as dramatic as the sighting by multiple witnesses in 1963 was seen again that decade.

We next pick up our story in the 1990s, a couple are driving towards the intersection at Black Tom’s Grave, but they don’t know that’s what the area is called. They’ve never heard of Black Tom. They’re visitors to Bedford. Both driver and passenger spot a man in what they think is an awfully good fancy dress costume. Dressed up in breeches and stockings, buckled shoes, a tailcoat and white shirt underneath. Possibly a pirate or highway man attire they think. He seems to be a little worse for drink, stumbling slightly. They slow down to get better look at the dandy gentleman, wondering what party or celebration he’s retuning from. When the fancy costumed pedestrian disappears into thin air in front of them, they shudder! They tell their tale to the friends they’re visiting in Bedford who realise that the disappearing fancy dress, drunk, they saw was crossing Black Tom’s Grave at the time.

There is another ghost sighting which has been linked to Black Tom, but it differs from the others in that it is a haunting inside a house. This took place in the 1980s and I have read a report as a comment to Black Tom’s story by someone who knew the people involved, as well as reading this account on paranormal databases.

A couple living on Gladstone Street, which is just to the east of Black Tom’s Grave, were troubled by a spectre. The man woke one night to see a shadowy figure outlined in the faint street light filtering through the closed curtains. He was so shocked he cried out, believing it to be an intruder. His wife woke and immediately saw what had started her husband. There was a shadowy cloaked man wearing a floppy hat standing in front of their window. The figure seemed not to be aware of them nor their shouts. They watched horrified as the phantom glided across the room and through the wall of their bedroom. The shadowy phantom in his floppy hat was seen on other occasions by the couple.

And there is one other curious account, which took place in a flat on Tavistock Street which of course intersects at Black Tom’s Grave. In this case the occupant of the flat reported poltergeist activity beginning with items being moved around his flat, furniture rearranging itself and even his records being played. One night he came home after work to find music playing when no one had been in the flat all day. With its proximity to Black Tom’s Grave, I thought I should include this story. It certainly seems that the Black Tom area of Bedford has had quite a lot of paranormal activity reported over the years.

Did Black Tom Exist?

I had high hopes when embarking on this story, to find an historical account of a highwayman nick named Black Tom. Possible newspaper reports or court records. But sadly, I found nothing. There are plenty of highway men, and robbers named Tom. But none match the details in the stories shared about him. This leads me to guess that the stories placing Black Tom in the 17th century, either dying or being born, around 1607 would make more sense as that means there’d be fewer contemporary records available. If he was a famous highwayman of the 18th or 19th century, I’m sure I’d have found some record of him in the newspapers and journals.

It’s also common for highwayman stories to become conflated, embroidered and in some cases wholly rewritten. Black Tom’s story could include aspects of other criminal’s exploits. He could be a figure head for many robbers and highwaymen of Bedford.

The most famous example of an embroidered and conflated highwayman story is that of Dick Turpin.

Yeah, you’ve heard of Dick Turpin and his horse Black Bess, he rode all the way from Kent to York in a day on poor Bess to create an alibi for a robbery he committed right? He was the most swashbuckling, dashing and the dandiest highwayman going. Every old inn between York and London has some tale of Dick Turpin. His ghost haunts so many lanes, copses, and ale houses it must be the busiest ghost there is going. His spirit must be spread so thin Dick Turpin won’t know which bit of him is where.

But what if I told you. Dick Turpin was the son of a butcher, had been a butcher himself selling dodgy meat he’d poached, he’d then become a burglar whose gang robbed and raped and bludgeoned their way to notoriety around Essex. Dick Turpin was a thug. Who even when he tried to go straight was what one historian referred to as an 18th century dodgy used car dealer, selling on stolen horses in York. He was caught by the authorities after shooting a chicken. He was a bully and a coward.

So why does the legend differ so greatly from the facts? Well, that’s quite simple in some ways and complex in others and understanding it may help us to understand why Black Tom’s story is remembered and yet facts are hard to come by.

In the case of Dick Turpin, his story began to evolve on the day of his execution when a ballad was hastily written about him including as much fiction as fact. Copies were sold to the people of York who attended his hanging. This wasn’t unusual if you’ve listened to the Potton Poisoner episodes, you’ll remember that broadside ballads were sold at executions throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, pretending to be confessions, life stories and actual poems written by the condemned. They were in fact written by enterprising printers and full of artistic licence.

When Turpin’s grave was robbed by body snatchers, just days after his execution, it just added to the fascination with his life and death.

A catchy song was written about Dick, about twenty years after his death and rather than focussing on how he’d been caught for shooting a chicken, how he’d sold stolen horses and dodgy meat, it focussed on his exploits as a highway man. Which he had been briefly after some of his gang had been caught for the burglaries and rapes.

And highwaymen were viewed as a cut above your usual criminal.

It seems since crime has existed human’s have had a fascination as well as a fear of it. And during the 18th and 19th centuries the British public loved true crime as much as they do nowadays. The true crime podcasts of their day were songs and ballads, books and then newspaper and journals publishing salacious details of real crimes and criminals. In the 18th Century several popular books appeared chronicling the deeds of British criminals of the past. And reading some of the accounts from them I was struck by how similar in some ways they are to the modern true crime genre.

They may not have the understanding of psychology or the terminology we have today yet, I noticed that 18th century accounts of criminals often start by saying that there were signs of trouble from an early age. The murderers and robbers were often unruly or disobedient children. Patterns of behaviour are chronicled but not dissected as we do today through a psychological lens.

And there is definitely a hierarchy of crime. And at the pinnacle of that hierarchy in the 18th century were highwaymen and women. (And there were highway women at least two, as well as a highway man who liked to dress as a woman but maybe we’ll explore that in a later episode.) Highwaymen were portrayed as celebrity criminals, dashing, and devilishly exciting. This was partly down to class. You had to have the ability to ride, get your hands on and properly look after a horse. Where a common footpad or robber could be anyone from any background. A highwayman was seen as being from a better class of person, with breeding and good manners.

And there were genuine highwaymen who were gallant, only stealing from the wealthy, treating their victims with courtesy, and even paying back those they robbed.

And although we remember nowadays some of their names and stories like Claude Duval the gallant French highwayman of restoration England making the ladies swoon. Many names are forgotten but their deeds have been collected and attributed to Dick Turpin. For example, the ride from Kent to York in one day, is said to have been achieved by William Nevison in the 17th century (though unlikely.) But the story stuck to Dick Turpin and in the early 19th century was well known enough to be part of his legend and included in a play about Turpin’s life.

As the years rolled on more highwayman stories stuck to Dick Turpin, like feathers in his cap. Until in the 1970s a completely fictional Turpin was the hero of a TV series I watched as a child. Although the series was set after the real Turpin’s death most who watched the show were unaware of that and thought the series was based at least in part on the real highwayman of the same name.

The Dick Turpin we think we know, is just a name now, a name that is associated with a fantastical collection of stories, hauntings, and landmarks. He represents not the actual man who bore his name but all highwaymen. He is a figure head a totem for highway robbers.

So maybe Black Tom, the real person, is lost to us in the mists of time but his exploits are not. And the idea of Black Tom is so powerful that it has outlived the historical facts and has given its name to an area of Bedford and the paranormal activity reported in that area.

Attitudes to Crime

Now in the 21st century we’re not immune to romanticising criminals including highwaymen. For one, highwaymen are seen as a distant type of criminal from a past we sugar coat with fancy fashion and ideas of gallantry. This way of viewing crime through different lenses, really struck me when I was searching for stories about Black Tom and the area that holds his name in Bedford. Because there was a recent horrific and deeply disturbing murder in that area.

In September 2018 16-year-old Cameron Yilmaz was brutally murdered by three 15 year old boys and a 19 year old in Bedford. The murderers filmed Cameron as he lay fatally injured, on snapchat and uploaded it to the internet. The murderers who were collectively sentenced to 71 years in prison were members of the Black Tom gang, living in the Black Tom area of Bedford. On reading the details of this case I felt despair for all the families involved. I felt confusion for why this happened, how it could happen.

It also made me think about why I and others would want to read about or tell stories about crime and criminals, whether of the past or present. And I think the answer lies in my reaction to that pointless murder of Cameron who had his whole life ahead of him. Confusion. We want to understand the world around us. We want to know how we fit into it and how others do. Trying to make sense of crime and why it happens is a way to try and reassure ourselves, that it is knowable, that there is some sense to the world, some justice some balance. But it does mean that we can oversimplify and embellish tales to make them fit more snugly into our world view.

Highwaymen genuinely terrified the travelling public for hundreds of years. Most were part of a gang. Many murdered as well as robbed, many injured their victims both physically and emotionally. Stories of their frightful deeds were popular at the time as lessons in how to avoid being robbed, in how to keep yourself safe. Some stories existed to reassure the public that not all highwaymen were violent some were gallant and noble. If you were lucky, it would be that type of highwayman you’d meet on the road. There was also the notion of a Robin Hood style highwayman, an outlaw redistributing wealth, balancing an out of kilter society. This aspect of the story was understandably popular with those who had little and felt the unfair grind of life daily. Most of the stories also end with the highwayman meeting justice. All is set right with the world again. It makes some kind of sense. It reassures.

I think it’s also why there are so many ghost stories associated with highwaymen and criminals in general. It’s as if we can’t let them just disappear. They can’t rest in peace because we can’t rest in peace. As long as there is crime and hurt in the world, unfairness and cruelty there will be some kind of psychic residue of it left behind. Or the unquiet spirits denied peace in death will roam restlessly. Because we’re restless; we as a society haven’t found a way to live with one another harmoniously.

The ghost stories live on to remind us, that the world is not always as it seems.

I’m not saying we shouldn’t tell stories that involve criminals or those who have committed terrible deeds either of the past or present. But I think we need to always remind ourselves that there are and were victims of these crimes. We should question why these figures are romanticised and why their stories live on far longer than the stories of their victims or the ordinary folk who had lucky escapes.

And the story of Black Tom is not all that it seems. But before I tell you about the twist in Black Tom’s Tale, there is one highway man more closely associated with Biggleswade I thought I could tell you about. Because his story can also shed light on Black Tom’s.

Shock Oliver

One aspect of highwayman folklore centres around the names of these outlaws. Many had nicknames. Galloping Dick, Blueskin Blake, the gallant Highwayman (Claude Duval) The Wicked Lady, and Swift Nick. Shock Oliver is a great outlaw name.

His actual name was James Oliver and reports from about 70 years or more after his death state that he was originally from St Neots, just up the great north road from Biggleswade. Some say he was the son of a baker, some a butcher. But it seems he soon lost interest in pursuing the family business.

An interesting aspect of his story is that his wife acted as an accomplice and source of intelligence for him. She may have been called Ann as I have found marriage for one James Oliver to an Ann in St Neots in the 1780s. But the legend has it that his wife worked as a cook, in the George Inn at Baldock. Baldock is just 8 miles southeast along the great north road from Biggleswade. And in the late 18th century the George was a busy coaching inn. Ann was in a great position to learn the comings and goings of folk heading both north and south along the road. Servants of wealthy travellers would have unwittingly shared details with her that she could then pass on to her husband and his gang. Shock Oliver’s Gang could then spring out on unsuspecting travellers demanding money, jewellery and fine fabrics and clothes.

One of the most famous stories about Shock Oliver that painted him in the light of a gallant highwayman comes from a memoir by George Race of Road Farm, Biggleswade (who lived from 1818 – 1911). Although Shock Oliver was executed 18 years before Race’s birth, he recounts the well-known tale of how Shock Oliver stopping a Dr McGrath on the road between Biggleswade and Sandy intent on robbery had a change of heart. McGrath was rushing to a gravely ill patient in Sandy and on learning this Shock Oliver allowed the Dr to pass unmolested.

Shock Oliver is said to have worked as a Highway Man for eleven years, understandably his favourite place to rob was the stretch of the great North Road between Baldock and St Neots, with Biggleswade right in the centre. He became a kind of folk hero after letting the doctor carry on to tend to his patient.

The details from Shock Oliver’s trial at the Hertford Assizes at the end of July 1800 make for different reading.

Oliver was up in front of the judge on 5 counts and was acquitted of the first on a technicality. It seems Shock Oliver plied his thievery across the country and there was a bounty on his head. Whilst in Dudley Worcestershire a Samuel Warwick recognised Shock Oliver and attempted to seize him. He fired a gun at Oliver but did not explain to him why. He gave Oliver no warning, just shot. Shock Oliver defended himself, firing a pistol back and then produced another gun, but this gun suffered a “flash in the pan” and a struggle broke out between the men. Shock Oliver brandished a knife and cut Samuel Warwick “in a shocking manner.” According to the Northampton Mercury reporting on 2nd August 1800.

The Judge acquitted Shock Oliver though, because Samuel Warwick had not declared why he was attempting to apprehend the highwayman. In the eyes of the law Shock Oliver was using reasonable force to defend himself against an unknown attacker.

However, there were four other crimes that Oliver was accused of. He was found guilty of the next on the list. He had fired a gun and attempted to rob a George Carter near Baldock. George and his companion a Mr Fossey resisted the robbery. Carter riding in one direction having recognised Shock Oliver and Fossey in the other. An alarm was raised, and Oliver apprehended. In later retellings of this daring ride away from the highwayman, it is Fossey who is shot at. But the contemporary sources are clear that it was Carter who was the victim at the trial. We do not know what Shock Oliver’s other crimes were because being found guilty of attempting to rob Carter and firing his pistol at him, he was sentenced to death.

Shock Oliver was hanged in Hertford at the beginning of August 1800. Later 19th and early 20th century reports say that Shock Oliver’s wife brought his coffin back to Baldock causing quite a public spectacle. One reporter says as a schoolboy he saw Shock Oliver’s coffin brought through Stevenage on a horse drawn cart. Oliver’s wife is described as sitting atop it, crying, and wailing in grief. The coffin then stayed over night in Baldock at the George Inn before being taken to St Neot’s for burial.

I haven’t found any ghost stories associated with Shock Oliver yet, but if he is going to haunt anywhere other than the A1 between Baldock and St Neots, it’s surely going to be the George Inn at Baldock where his coffin rested with his wife overnight. The place where he gained much of his intelligence.

So, although we know James Oliver was a real highwayman, charged and executed for his crimes, his story has grown since his execution. Articles about him appear in the 1870s, 80s and the 1900s each adding pieces to the picture. Nowadays you can read his story on blogs about old Baldock and the George Inn. And in Biggleswade, school children designed a mosaic which is on the main bridge over the railway on Biggleswade High Street that depicts Shock Oliver on his horse, firing his gun. There is no flash in the pan this time. There’ll be a photograph of it and others on the show blog. Weirdinthewade.blog

Could Black Tom have been a similar character, a highway man who was willing to fight for his life when in danger, prepared to fight to get the loot he was after, but a generous soul who would allow those in need and the poor to slip away?

You see the curious thing about Black Tom, beyond the fact that I can’t find any historical version of him, is that there are sometimes two ghosts seen at his grave. Could there be two Black Tom’s of Bedford?

Well maybe there were, because there is an historical character called Tom with connections to Bedford whose deeds were so evil, they are still remembered nearly 1000 years after he lived. His name is Thomas Dun, and some claim the Bedfordshire town of Dunstable is named not after him but named after the King’s attempt to capture him. The legend states that Dunstable was founded as a garrison to capture this Thomas Dun. His life story reads like a nightmare but is also infused with folklore tropes and imagery which make it hard to interpret what was really going on.

Up Next on Weird in the Wade

In the next episode of Weird in the Wade we’ll explore the story of Thomas Dun and investigate if his ghost is also haunting Black Tom’s Grave. We’ll ponder why so many hauntings are connected to crimes, criminals, and their victims. I’m hoping to speak with a very special guest to shed some light on this and we’ll explore local stories like that of Galloping Dick another Bedfordshire highwayman, and others from further afield including a heartbroken spectre searching for his stolen goods, and stories of crime from north of the border in Scotland. All next time on Weird in the Wade!

But before you go just some information on the sources I used for this episode and how the story of Black Tom differs in different retellings. A full list of my sources can be found on the blog weirdinthewade.blog. But I found Black Tom’s story in many Bedfordshire ghost story books from Damien O’Dell to Betty Puttick, it’s also covered on various blogs, YouTube videos and paranormal databases. The retelling of his story since the 1980s seems to be that Black Tom was a highwayman who was captured and although the residents of Bedford petitioned for a pardon, he was denied it by the evil gaoler. He was buried at Black Tom’s Grave because that’s where he was hanged. Why he had a stake through his heart isn’t adequately explained.

The earliest version of his story that I could find dated from 1941 differs by stating that Black Tom had drowned in the river Great Ouse whilst trying to escape the sheriff’s men and was buried at the junction with a stake through his heart because his death was deemed a suicide.

So, I took a bit of a story telling liberty by merging the two versions of the tale into one. In my version, Black Tom jumps into the rive to escape his pursuers but he does not drown. I thought that just being an outlaw, or a tragic suicide didn’t really explain why his story had lived so long in the local folklore nor why he would have had a stake driven through his heart. But if he was deemed to have survived a drowning and was hated by the Sheriff and the gaoler, then being buried with a stake through his heart made much more sense!

I hope you forgive my embroidering of the tale, but that’s how folklore evolves and stays relevant, I think. In the retelling and reimagining of the stories.

Thank you for listening to Weird in the Wade. I know there are quite a few new listeners who have found the show through the Uncanny Community on Facebook as well Twitter since December. You are all very welcome to this weird corner of the world indeed.

And talking of Uncanny, those of you local to Biggleswade there are new Uncanny Live tour dates including one in Peterborough and one in London, so both are pretty easy to get to on the train from Biggleswade. I saw the Uncanny Live show in Cambridge in November, and I enjoyed it so much I am going to see it again in Peterborough in July. I even met up with a couple of listeners to WitW at the Cambridge event which was super exciting!

Thank you so much everyone for listening and joining in with the Weird in the Wade social media. You can find Weird in the Wade on Twitter or X, Threads, Instagram and Bluesky. Don’t forget to check out the blog which is weirdinthewade.blog There’s links to all the socials in the show description where you’re currently listening.

I have some very exciting plans for this coming year for the show including some guests and really interesting stories. Your support means the world to me. If you can share, rate or review the show if you haven’t already that would be amazing. It really does help more people find the podcast. And thank you to all of you who have rated and reviewed the show. Across Apple and Spotify the weird in the wade has over 50 5 star ratings now, which is just amazing. Thank you.

I do have a Ko-Fi page for the show. Ko-fi is a website which enables listeners to buy the show a coffee or two. All the money I raise goes back into the show, paying for equipment, travel expenses, podcast hosting and music payments. So anything you can spare really helps the show to keep going and develop. Thank you to all of you who have supported via Ko-fi in the last month including anonymous donors and Fiona, Michelle and Lorna. Thank you so much!

Don’t forget if you have any questions, suggestions or just want to get in touch you can also email the show at weirdinthewade@gmail.com

WitW is researched, written and presented by me Nat Doig.

Theme tune is by Tess Savigear.

All additional music and sound effects from Epidemic Sound.