Notes and Links

Articles about broadside ballads which mention Sarah Dazley”s case can be found here:

https://www.mustrad.org.uk/articles/bbals_02.htm

https://www.mustrad.org.uk/articles/bbals_04.htm

Execution ballads also appear in this episode of the Folklore Podcast: http://www.thefolklorepodcast.com/episode-132.html

News article about execution memento sold at auction: https://www.bedfordindependent.co.uk/souvenir-of-last-person-to-be-publicly-hanged-at-bedford-gaol-smashes-pre-sale-estimate-selling-for-2250/

Transcript

Part 3 of the Potton Poisoner

Hi, Nat Doig, here, this is the third and final part to the Potton Poisoner story, if you haven’t listened to part one or two yet, I’d recommend you go back and start there. I’ll still be here waiting when you’re ready.

Also, just a heads up that although this is about a case that is 180 years old it covers an infant death, murder, and domestic violence and abuse. I’m letting you know so you can decide when and how you listen.

Haymaking

It’s July 1842 and George Waldock is resting after a long day hay making alongside the whole village it seems. It really is a case of making hay while the sun shines. They need the hay to feed the livestock through the winter.

The other occupants of George’s home are either fast asleep upstairs or easing their aching muscles and bellies with beer and a hearty supper in the local pubs of Cockayne Hatley or Wrestlingworth. But George chose to stay at home this evening because Sarah Dazley is visiting, to mend his shirts.

George tells himself he’s not the settling down type. He’s currently courting Mary Carver, but he thinks it will be just a dalliance, though Mary is sweet on him. He’s also caught the eye of little Mercy Meaks, she may be young but she’s not shy, and she is very pretty. But now watching Sarah sitting by the open window for the last of the light, her head bent over her sewing, the setting sun a glow through her fiery auburn hair, he wonders if married life is not such a bad thing after all?

So he asks Sarah: How are you finding married life then?

She looks up at George, her hazel eyes gleaming in the dying light and replies in that slightly dramatic way of hers, that the village women mock her for behind her back: “Very well. I am glad I have a good husband, but he is always ailing and will soon be in the church yard I fear and I shall be very happy to follow him there.”

Well, that’s how George recalls the conversation in March 1843 in front of the coroner and jury at the inquest into Sarah’s second husband William Dazley’s death. Fast forward to July the same year and in front of a judge and jury at William Dazley’s murder trial he remembers it like this:

Fast forward noise

How are you finding married life then?

“Very well. I have a very good husband, but I wish he was dead, he will soon be in the church yard, and I shall be very happy to follow him there.”

Some changes in recollection can be forgiven over the passage of time, and there are many when you compare the inquest reports to those of the murder trial. But when a recollection changes from something that sounds reasonable and plausible, to something far more fantastic, you have to ask yourself why? Which version is the truth? What could have motivated George to lie either at the inquest or the trial? And untangling it all becomes incredibly tricky.

If George’s first statement at the inquest was a lie, did he lie to play down the incriminating statement that Sarah wanted her husband dead, out of a vestige of loyalty or love for her? He’d only called off their marriage some few weeks before.

Equally could he be lying at the trial in the July because over the intervening months he’s become certain that she did poison both her husbands and her child? This recollection fits with his new opinion of her. Also could his loyalties have changed? Is it in his interests to have Sarah convicted; his evidence now neatly condemns her?

Personally, I think it’s far more likely that his statement in July is the false one. That He shaped his evidence to match the crime she is accused of, rather than just recalling their conversation.

What we’ll try to do during this final episode of the Potton Poisoner, is pick a course through all the evidence whether it is clear, or contradictory, uncertain or categorical, and try to decide what really happened to William Dazley in 1842. Welcome to this final episode of the Potton Poisoner from Weird in the Wade.

Introduction

Previously we heard about Sarah Daszley’s life and how she responded to accusations of murder. We looked at how the press treated her, why arsenic poisonings were such an issue for the Victorians, and how their attitudes to women and violence in the home affected this case. We also followed the inquests into Sarah Dazley’s first husband and child.

In this episode I’m going to take you through month by month what we know happened in 1842 and 3 in the run up to and aftermath of Sarah’s second husband, William’s death. I’ll let you know where the evidence is different between the inquest and the trial. When I don’t point out any changes, you can assume that the evidence was corroborated or not challenged in any way. I think it’s the best way to bring to life some very twisty testimony and understand the complexities of the case, but it also shines a light on where we have huge holes in the timeline and the evidence. We’ll also look at Sarah’s execution and what happened to many of the various people you have met through the last three episodes. And finally, I have a new ghost story associated with Sarah to tell.

I’m Nat Doig and I hope you enjoy this final episode of the Potton Poisoner.

Harvest

August was another busy month, of harvesting. Many who would not normally work in the fields left their jobs or school and joined the bringing in of the crops. It was a time of extreme hard work, but also of freedom, to be in the fields with your friends gossiping and singing and generally trying to make the back breaking work go faster. It was also a traditional time of courting or the beginning or end of love affairs.

George and Mary Carver are now seeing more of each other. Though when Mary is cross examined about this relationship at William’s murder trial, she plays it down.

“Yes, I was sweet on George but I did not expect marriage”

This is quite the admission, for middle class Victorian Britian to read, and possibly was for some of the more traditional and religious working-class folk. Mary Carver is admitting that she entered into a dalliance with George without expecting the respectability of marriage as her reward. She paints herself as a loose woman and why is she prepared to do this? Because she does not want to be portrayed as the jilted lover, jaded with jealousy who would spread gossip and lies about her rival Sarah.

During August William Dazley is also out bringing in the harvest. But he is not feeling quite himself. He complains of being unwell and numerous people at the inquest and the trial say he was poorly. William Dazley was not a well man from harvest time until his death. The nature of his illness is never specified just that he was ailing.

Sarah is not working in the fields at least for some of the time, though I get the impression that she was not the type of woman to have worked labouring in the fields if she could help it. As well as her sewing services, she is also working for the Gurry’s in their local shop. Ebenezer Gurry and his wife also a Sarah, run a bakers and general stores in Wrestlingworth. Mrs Gurry also sees herself as a local healing woman. She stocks all kinds of pills, powders and potions bought in from the druggists in nearby towns like Biggleswade. She also makes up remedies herself and will visit the sick providing a cheaper alternative to the local doctors. Including remedies the medical men do not approve of, things like leeches.

Sarah Dazley mainly runs errands for Mrs Gurry but also on occasions serves in the shop. The newspapers make much of how Sarah learnt about poisons and potions in the backroom of the Gurry’s general store. But Mrs Gurry denies this. Her evidence is clear, Sarah ran errands and served in the shop. She was not some apprentice druggist or apothecary.

One of these errands was to Sarah’s hometown of Potton to buy ingredients from a chemist there. A young shop boy, named Robert Norman, remembers a conversation between his boss John Burnham and Sarah like this:

JB: Good morning, Sarah, yes, yes it’s very dusty out there! It’s the demolition of the old bake house, dust everywhere! How can I help?

SD: Good morning, Mr Burnham, oh and hello Robert, I didn’t see you there. Give my regards to your parents!

RN: Thank you Ma’am.

SD: Mr Burnham, I’ve got a list here from Mrs Gurry and its as usual except I also need half an ounce of arsenic powder.

JB: Right you are. Mmm Arsenic, what’s that going to be used for then?

SD: Well, killing rats of course.

JB: Right you are. Look here I’ll write POISON in capitals very clear like so no one can be mistaken for what it is.

We do not know if the poison was for Sarah’s own use or for Mrs Gurry’s and as you’ll find out later, Mr Burnham believes that this all took place much later in the year on the first day of William’s illness. I’m inclined to believe little Robert’s timings though, because he pins it to the demolition of the bakehouse, an actual thing that happened. But as both agree that arsenic was bought, I believe we must admit that Sarah did buy arsenic from a chemist either for herself or for Mrs Gurry.

Michaelmas

Michaelmas falls at the end of September and in the 19th century it was an important date. It was the time of year that farm labourers renewed their hiring contracts or found new ones. Fairs were held around the country where this hiring process took place. It was a good chance to let off steam after the harvest, catch up with friends and family, and there would be festivities and games centred around the fair.

In 1842 Sarah Dazley went to the Michaelmas fare in Potton by herself. We have no explanation for why William did not join her. All we know is that he forbade her to go, and she went anyway. Possibly this illness that had affected him since the harvest time kept him at home.

The day after the Michaelmas fair an argument between the couple erupted. It was so heated that passersby remembered hearing the argument coming from the Dazley’s home, whilst on the street.

A neighbour of the Dazeley’s John Hanley who worked as a thatcher gave testimony at the inquest that the couple had quarrelled eventually taking the argument outside their house, that blows were struck and both were physical towards each other. At the trial John goes further and says that Sarah in a bid to escape William, sought refuge in his home, which he gave but eventually William became so enraged that he marched into John Hanley’s house and dragged Sarah outside and hit her.

It was after this that the injured Sarah was heard to say:

“I don’t care a damn for such a man as you! I’ll be a match for you some day. Blast you!”

Sadly, as we discovered in the last episode this is not the first time Sarah had faced violence from a spouse. Yet the newspapers of the time seem more outraged by her language, for saying damn and blast, than they are for the violence she has been subjected to.

This appears to be a turning point in Sarah’s life. It is reported that she said from this day:

“I never took him his dinner afterwards and never fetched him his beer for supper nor wouldn’t afterwards if he had lived for twenty years.”

Withholding these wifely duties was her act of revenge she claims, not poisoning him.

October the week of illness. Pills, pigs and powders.

Saturday

On Saturday 22nd October 1843 we’re back in that chemist shop in Potton run by Mr Burnham. He has a record of Sarah Dazley coming in with a shopping list from Mrs Gurry. She bought treacle, syrup of rhubarb and a pound of black lead. He seems to have meticulous records of all he sold. Yet, although he claims it was this day that Sarah bought arsenic, he has no record of it. Which is why I’m inclined to believe little Robert’s account that the arsenic was bought much earlier in the summer.

When Sarah returns home with the goods for Mrs Gurry, she discovers that William is now quite ill. Poorly enough for his parents to be with him. It is in the afternoon that Sarah discovers that a Dr is passing through the village, and she rushes out into the street to waylay him and beg him to come see her husband too.

Dr Sandell was originally from Chester but settled in Potton sometime after 1841. He has a small family at this stage and is described as a general practitioner, serving Potton and its surrounding villages.

Sandell reports that William was sick with an irritation of the bowels what we’d probably call today a sickness bug. He prescribes a powder of carbonate of soda and tartaric acid. Basically, a version of alka seltzer or other hangover or sickness medicine that can be bought to this day over the counter. He sends the medicine with a messenger once he is home.

Tuesday

Dr Sandell visits the Dazley house to check up on his patient. William is doing a little better and so again Dr Sandell sends a powder which is of a yellow colour and this time made up of rhubarb and ginger. A classic combination to prevent sickness.

Living in the house with Willaim and Sarah is little Anne Mead. She is 13 or 14 at the time and the sister of Sarah’s first husband Simeon. Anne is there to help about the house and may well have been living with them since 1840 when little Jonah was still alive.

Anne tells the inquest that on the Tuesday morning she witnessed Sarah making up three pills in the kitchen. She describes them as large and dark, and that Saarh wrapped them in newspaper and hid them in her skirts.

But if we fast forward to the murder trial Anne is no longer certain if this happened on the Tuesday or the Wednesday morning.

Similarly at the inquest Mary Carver tells a tale of visiting Potton with Sarah to see Dr Sandell but at the trial she says it was the Wednesday. And because other witnesses tie this trip to Potton to the Wednesday, I’ll give Mary the benefit of the doubt that she simply misremembered at the inquest or that the newspaper reports just got it wrong.

Wednesday

Maybe it was this morning that little Anne Mead saw Sarah make up the pills.

Dr Sandell visits once more and is happy with his patient’s progress. He asks Sarah to come and collect a stomach mixture as a tonic from Potton, later that day.

Sarah certainly travelled to Potton to collect this mixture from Dr Sandell. He has the record in his books. But other witnesses including Mary Carver say that Sandell also sold her some pills. Opiate pills called resting pills. Sarah herself told Fanny Simmons and Mary Anne Nibbs, the women who chaperoned her on her last night of freedom, that Sandell refused to sell her any resting pills. And Sandell seems to want to agree with this.

At the trial he is uncertain if he sold her resting pills or not. He has checked his records and the sale is not in his daybook. But he concedes that he could have sold her the pills. He concedes that by Wednesday morning William was in a state in which resting pills may well have helped him.

It’s confusing to say the least.

Now we must turn to the evidence of Marcy Carver. Although she changes the day that this happens, she does not change what she says happened.

She claims that on the way home from Potton, Sarah took out the pills given to her by DR Sandell (the ones he has no record of or recollection of selling her) and chucked them in a ditch! Sarah then produced three larger pills which she replaced in the pill box. She claimed that these pills were from Mrs Gurry and would do a better job than those prescribed by Dr Sandell. I’m not sure what the deal is with these resting pills, why Mary Carver is so insistent that Sarah was given them and then threw them away. Is she just wanting to incriminate Sarah? Surely, she could do that without an elaborate story about Dr Sandell’s medication.

Especially as Mrs Gurry confirms that she did give Sarah three anti bilious pills. At the trial she goes further and says that these pills were from a batch she had bought from Barkers of Biggleswade to sell in her shop.

Now Barker was a druggist based on the high street in Biggleswade. He sold all kinds of pills and potions and advertised in local newspapers about some of the more discrete medications that he sold, including treatments for syphilis that included mercury and arsenic as ingredients. I’ve found advertisements for wonder cures of this sort from him in the 1830s -50s. Often purporting to be from exotic locations, Dr so and so’s Austrian cure. Who knows what were in Barker’s anti-bilious pills or where he got them from. Maybe they were just more carbonate of sodar or ginger. But in his shop, he clearly stocked medications that included poisonous ingredients. Mrs Gurry says she does not use arsenic in her medicines but what of the ones she bought in? Sadly, we do not hear whether Barkers was ever searched. Or if the remainder of Mrs Gurry’s batch of Barkers pills were ever tested. She simply says she handed them to the coroner at the first inquest back in March and never saw or heard about them again.

Back to Wednesday 26th October, Sarah returns home with three pills. We never hear for sure whether they were Dr Sandells pills, Mrs Gurry’s or the ones Anne Mead says Sarah made that morning. The only clue we have is that when Mrs Gurry confirms that she gave Sarah three pills, Sarah becomes emotional. But we don’t know why, is it relief or anguish.

But whoever supplied the pills there were three of them. And William refused to take a single one. Sarah tried, but he is described by more than one witness as being like a child in refusing to take medicines.

Sarah gave up and went out on further errands.

Anne Mead decided that she would try to coax William to take one. She explained it like this:

Well, if he was going to behave like a child I would treat him like a child and I took one of the pills right in front of him, saying See I take the medicine you can too William. And he did he took a pill in front of me.

At the inquest she says he took all of his medicine, at the trial Anne says he took one. Leaving a spare.

Either way within an hour poor Anne Mead is sick with a raging headache and vomiting. When Sarah returns home and asks what is wrong, she scolds Anne for taking medicine not meant for her. Anne is so distraught and poorly she leaves the house for her uncle and aunts. So, she was not so incapacitated that she could not walk.

Did little Anne take a resting pill of opium which made her feel so unwell? Or was it a pill from Mrs Gurry’s meant for a grown man who is suffering from sickness? Or was it arsenic made up by Sarah? We honestly don’t know.

One other curious thing happens that night and a warning here this gets a bit gross. William is sick again. Though not seriously. But a bucket of vomit is produced and needs to be discarded. William’s Mum empties it into the front yard and thinks no more of it until the next morning.

Thursday

Elizabeth Dazely finds the body of a pig in the front yard. Swollen up like a bladder and dead. It is assumed by all that the pig died by eating William’s vomit. The pig it turns out belongs to the Gurry’s who also own the house that the Dazely’s rent. When Sarah learns of the pig’s demise, she advises Elizabeth to in future discard of any vomit in the back yard away from the pigs.

Elizabeth doesn’t mention the dead pig to anyone until the trial. It’s not raised at the inquest and she didn’t raise it at the time to the Dr. She admits under cross examination that she just assumed that whatever illness William had could be transferred between him and the pig. It was far more common then for people to live closely with animals like pigs and many diseases were passed between both. Although Sarah’s instructions could be interpreted as her having knowledge about poison, they could also be just as Elizabeth initially feared that whatever ailed William was contagious and could be passed on to others including pigs.

Dr Sandell visits again on the Thursday. He is still happy with his patient’s progress, but not it seems that William now has leeches on his neck and the Gurry’s are fussing over him. William’s Mum has also put a poultice on his stomach.

And here’s a thing. No one mentions the leeches dying. Yet if they’d fed on William’s blood and he had taken arsenic the day before, it would have surely killed the leeches too. I think Dr Sandell includes this detail to demonstrate just that.

Saturday

By Saturday all agree that William is doing much better. He has been out of bed and cheerful. Dr Sandell visits and is happy with the progress being made. He invites Sarah to come to Potton and collect some more medication, it is again the powder of rhubarb and ginger which Sandell insists is yellow.

Sarah travels to Potton and collects the powder. They are both so impressed by William’s recovery that Sarah asks Sandell to make up the bill for early next week and he agrees.

Saturday evening 8pm

William’s parents have gone home relieved that their son will be alright. But his two brothers, 19-year-old John and 16 year old Gilbert remain.

After Anne Mead’s departure, Mary Bull has joined the house to help out. So, she is there, as are both the Gurry’s and Sarah.

It appears they are in and out of the sick room, which is Sarah, and William’s bedroom.

Sarah says she has the final powder from Sandell to give William.

Mary Bull remembers her saying:

“Dr Sandell says he must take this powder, or he won’t get better”

At the inquest John remembers Sarah saying it like this:

Dr Sandell says this powder may make your feel better, but it could make you feel worse.

16-year-old Gilbert however remembers it like this:

Dr Sandell said if the powder operated right then he would soon be better and if wrong he would soon be dead.

Welcome to Saturday night where no one agrees on anything.

John and Gilbert both claim that they see Sarah make up a mixture from a white powder in a teacup and some warm water from the tea pot. They claim this at the inquest, and it goes unchallenged because there is no defence to cross examine.

Fast forward to the murder trial and Mary Bull says:

The brothers were not in the room when the powder was put in the teacup nor made up. I was not in the room when it was made up and nor were they. I was sent from the room.

According to Mary they all entered the room afterwards and by that point there was a teacup which had diluted powder in it. No one could say for certain where the powder had come from or who put it in the teacup, but Sarah was helping William to drink it.

The Dazley brothers however, say they saw Sarah take the white powder from a packet in her bosom and that there was also powder spilled on the table and that table was right next to where they were standing.

Mary denies all this too. They weren’t in the room to see where the powder came from and when they did enter the room, she says the table was on the other side of the bed, the boys were not standing where they say they were.

Mary and the brothers are in agreement though that Sarah had a powder, once diluted in water it was given to William.

They all agree that the Gurry’s were in the room.

Yet maddeningly the newspapers don’t report what the Gurry’s have to say about this powder.

It’s so frustrating.

By 9:15 William is very sick again and his parents are sent for.

He dies in the early hours of Sunday with his parents, brothers, the Gurry’s and Sarah at his side.

Monday

Dr Sandell learns of William’s death and is astonished. He rushes over to Wrestlingworth not believing it is true. There he finds Sarah quote “making much fuss and crying” whilst Elizabeth Dazley is angry with him he feels. Sarah however must have calmed herself enough to tell him that she is satisfied with everything he did for William and that he should not blame himself.

He suggests they could open up the body to try and find out what has caused this turn of events. Both women refuse.

He says at the trial that up until Saturday William’s illness had taken what he saw as a natural course. William was very sick, he gradually got better through the week and was well on the mend. He even goes as far to say that he does not believe William was poisoned earlier in the week only on the Saturday. But even today it’s notoriously tricky to work out when poison has been administered. He could have been given a lower dose earlier in the week. And surely Sandell would prefer to believe that rather than be known as the Dr who treated a poison victim for over a week without even realising what was going on? But then I think of those leeches and how deadly arsenic is. Surely there was no arsenic in William when they were feeding on his blood.

On that Monday Sandell gives up persuading for an autopsy and leaves the family to their grief.

November / December

Winter is drawing in and William has been buried in the churchyard.

George Waldock has dropped his dalliance with Mary Carver. She’s not sure why but he’s spending more time with that widow Dazley.

What neither Sarah nor Mary Carver know is that George is also spending a lot of time with 16-year-old Mercy Meaks. She lives in the same cottage as William Dazley’s brother John up at Cockayne Hatley farm near to George’s home.

It’s around this time in late November that Mary Carver tells someone that she thinks Sarah Dazley poisoned her husband. But her story is dismissed as gossip from a girl just jilted by George who always had a soft spot for that Sarah Dazley who he’s now wooing.

But a rumour like this one, whoever started it, begins to spread. To have had two husbands die under strange illnesses is unfortunate, could it really be a coincidence? Didn’t someone recently hear Sarah say that at this rate she’d have 7 husbands in 7 years or was it 10 husbands in 10 years? Makes you wonder.

Christmas Eve

Despite the gossip which both Sarah and George have heard, George asks Sarah to court him formally on Christmas Eve, he promises in the new year he will have the banns read in church. George is to become Sarah Dazely’s third husband.

January

The first banns are read in church.

February and early March

The second banns are read out in church but this time to whispers.

It’s too much, George confronts Sarah he demands that she give an account of herself because the rumours are growing and spreading.

George says she is defiant:

I did not poison anyone, you knew these rumours before you proposed, you need to make your mind up George Waldock and stand with me or not at all.

But she does do something about the rumours. She goes to Dr Sandell and asks for a letter of good character, saying that she was nothing but a good wife to William throughout his illness. And Dr Sandell obliges. Even though he wanted to open up the body and felt the death was suspicious, it appears he did not suspect Sarah.

Sarah also puts it about the village that she is happy for the body of William to be dug up, she thinks it should be done. Then they’ll know for sure that she did not poison him.

But this is not enough for George. A little while later he says his team in the fields are ribbing him, saying he was in on the poisoning. He helped so he could snag himself a beautiful wife. And so, he goes to the vicar, and he calls off the wedding forbidding the reading of the final banns of marriage.

Sarah meanwhile hears a rumour that little Mercy Meaks up at Cockayne Hatley farm is pregnant or as the witnesses in court say coyly, in the family way. And that George Waldock is the father. She is furious. To her this all now makes sense. Geroge’s sudden loss of interest in marrying her. His sudden belief in the rumours he had previously been dismissing. All of it is to get out of the marriage, not because he believes she poisoned anyone but because he wants to marry Mercy Meaks after getting her pregnant!

She confronts George and just as he denies it in court, he denies to Sarah. He says that he doesn’t know anything about this Mercy Meaks being in the family way. Yes, he knows her and has spent time with her he admits in court, but he’s got no idea about this pregnancy.

And whilst Sarah and George are arguing after he forbade the banns, Reverend Twiss and the magistrate Francis Pym call in the coroner because unlike the villagers who are content to gossip, these officials want actual answers.

And as we know, Sarah runs off to London in the company of another man, arsenic is found in William’s remains and as Mrs Gurry, Sarah’s friend, landlady and employer says about all of this “It’s looking very dark for Sarah, it’s looking very dark indeed.”

And before we look at prosecution and defence summing ups at the trial I’m going to let you in on a secret, something none of the jury or the officials at the court could possibly have known because it was yet to happen.

One year after the murder trial of Sarah Dazley. George Waldock gets married. He marries Mercy Meaks, now aged 18. I could find no record for a child born with Mercy as a mother in 1843 nor with George given as a father. But there is a fairly mysterious Waldock child baptised in Biggleswade into a large branch of the Waldock family with no mother nor father’s name apparent. And what makes matters even harder, is that this Biggleswade branch of the Waldock’s emigrate to Australia in the 1840s to become early pioneers in that country. And in 1850 Mercy and George join them. I’ll tell you more about their life in Australia later, but it means I can’t look at UK census records to see if they have a child living with them of the right age to have been born in 1843. But it’s fairly safe to say that the rumours about George and Mercy were probably true.

The trial

At the inquest into William’s death there was no prosecution and defence as such. The jury were active and able to ask questions of witnesses beyond what the coroner would ask. We learn that they question Mrs Gurry very closely about the keeping of arsenic. As I’m relying on newspaper reports I don’t know what else was asked and there’s a whole wealth of evidence that they don’t report. The jury in the inquest only deliberate for a few minutes before declaring that William died of arsenic poison, administered to him deliberately by the hand of his wife.

The trial is slightly different. There is a judge. Sir Edward Alderson and two prosecuting lawyers Pendergast and Gunning. Sarah is also entitled to a defence lawyer thanks to a recent change in the law. She is defended by Mr O’Malley who is deeply unhappy at the predicament he finds himself in. He gives a grovelling and apologetic speech to the Judge and Jury explaining that he has been denied the evidence he needs to build a defence. He appears to not have been able to interview Sarah nor had access to much of the evidence the prosecution has. He claims he only agreed to the task because the Judge is such a fine one and he feels that justice can prevail if the Judge makes up for his shortcomings. It’s quite pitiful to read and I think was to make a wider point about the conditions defence lawyers worked in when representing clients with now means to pay them. It sounds like he was appointed only that morning or at least only a day or so before the case.

Saying that it’s thanks to O’Malley that some of the inconsistencies in evidence are uncovered. He also does as good a job as he can at summing up and pointing out the holes in the prosecution.

The prosecution relies on paining Sarah as an unhappy wife who had been telling people for months that she was going to do away with her husband. The motive they say is that she wanted to move on to the next man, George Waldock, the means is that she had bought arsenic so had it at her disposal. (Just about every household in the country had arsenic at their disposal though.) They also rely heavily on the evidence of the white powder in the teacup. She gave her husband this powder so she must have poisoned it. Then there was Anne Mead being sick and Sarah scolding her, plus the dead pig. The prosecution relied on here say and rumour but they did also have strong circumstantial evidence. Unlike with accidental arsenic poisonings there seemed to be no source for accidental contamination. No one else had fallen ill apart from Anne. If there was arsenic poison in Sandell’s medicine or that of the Gurry’s pills, then surely someone else would have been ill at around that time?

The trouble is we don’t know, and O’Malley had no time or means to go out and find out. Maybe a group of people taking Barker’s pills did fall ill in Biggleswade? We also don’t know if the pills Mrs Gurry handed over to the coroner were ever tested.

The defence on the other hand has little to put forward as an alternative narrative. They don’t point the finger at anyone else though I have read modern reports that say Sarah’s defence did claim William killed himself. I think if this was the case, it may have been suggested merely as statistically more likely than murder. I’ve also read that it was claimed that William poisoned baby Jonah and then either killed himself in regret or Sarah killed him in revenge.

But if O’Malley said this its not in the newspaper reports I’ve read. Instead, O’Malley does points out that:

much of the evidence is rumour or here say that cannot be corroborated.

much of the evidence contradicts other evidence. William was sickly, William was in fine health. The Dazley boys saw everything, they weren’t even in the room.

there is no compelling evidence that Sarah was ever cruel to her husband or to anyone else for that matter. Most witnesses say she was happy with William.

He counters the reports that Sarah had sworn at her husband and spoken ill of him by pointing out that she only did this once she had been assaulted by her husband and O’Malley says that if there is one thing guaranteed to upset a woman it is rough treatment by her husband. He points out we all say rash things in anger.

Lastly, he relies on the Victorian trope, that a woman is not capable of such evil as murder.

As we discovered in the last episode, the Victorian’s had a contradictory opinion on the nature of women. Yes, many believed women were naturally gentle and nurturing, incapable of great violence and harm. But many also believed that women were uniquely weak to temptation and sin and so could be easily corrupted into becoming an unnatural woman and that was really, what O’Malley was fighting against. The prosecution saw Sarah as an unnatural wife, a woman who poisoned to get out of one marriage and into another. She could not control herself just as they claimed she could not control her temper or her sexual appetites. Just look at the temptress.

To simply counter that by saying, “Oh nonsense everyone knows women are incapable of murder” was just ridiculous I think even for the times, most Victorians would have seen straight through it.

The judge does I feel give a fair summing up. He reminds the jury that even though an inquest has found her guilty this court has a higher burden of proof, and they must have no reasonable doubt. He emphasises that this could have been an accident and they must be certain that it wasn’t.

At the start of the proceedings, we know that Sarah pleaded emphatically that she was not guilty.

The jury retires for just a quarter of an hour and then return with their verdict. Which is that they find Sarah Dazley guilty of the murder of her husband William.

The description of Judge Alderson’s reaction to the verdict is heart breaking. He apparently sat with his head in his hands trembling for some minutes uncontrollably. When he recovered his composure, he asked Sarah if she had any words before he sentenced her to death, and she replied:

But I am not guilty your honour.

Alberson was then so overcome with shaking that the black coif he had to wear to pronounce a death sentence fell from his head and had to be replaced.

He pleaded with Sarah to make her confession to God.

It turns out that Sir Edward Alderson was a very famous and well renowned judge of the time specialising in financial law, but he heard many criminal cases through the cycle of the assizes. He was famous for convicting the luddites and chartists, he was a conservative against social uprising. But he also believed that rehabilitation was more important than punishment. He was well known for saying that capital punishment was not a deterrent to crime and wherever possible he would avoid pronouncing a death sentence, finding creative ways to work around it. I think he tried to make the jury understand that the level of doubt for this case was too great to convict for murder. But he was up against months of reporting in the papers as fact that Sarah was a multiple murderer. Maybe if Sarah had confessed, he would have found a way to demonstrate how contrite she was and have banished her to Australia instead. But she didn’t confess. Not even at her execution.

Sarah Dazley went to her death proclaiming her innocence.

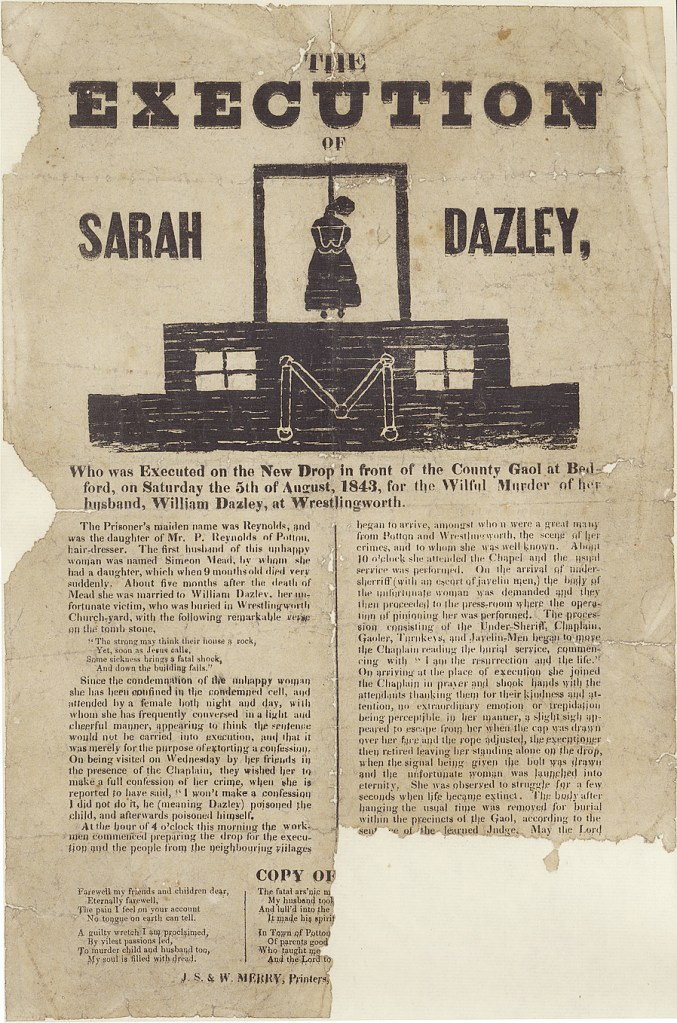

Execution

It was rare for a prisoner sentenced to death to not confess to their crimes. Many gave in and spilled their sins to the chaplains or warders at the gaol. Few in 19th Century Britain were executed refusing to admit their guilt. The belief in Christianity was strong and by confession in this life they hoped for forgiveness for the next. Or some just saw that they had nothing to lose now. Appealing a conviction was not an option and a pardon could be awarded in certain circumstances, if they admitted guilt and there was some mitigating factor, then the home secretary could pardon a death sentence but not the conviction.

So, Sarah went to her death on Saturday 4th August 1843, at Bromham Corner outside Bedford Gaol still saying that she was innocent.

Over 10,000 people turned up to view this public hanging. And Wiliam Calcraft the famous early Victorian executioner was the hang man.

By all accounts the crowd was calm, quiet, and respectful in the build up to the act. But on her neck being broken by the noose, the crowd erupted, and Bedford then suffered the drunkenness and revelling such events brought. A report describes debaucheries such as “drinking, smoking, hustling and singing” all on display. There is a particular description of “vagabond ballad-mongers bawling out the last dying speech and confessions and singing the copy of verses made by the woman (Sarah) herself. All of which we need not add was entirely false and got up on the occasion by a printer in the town as harvest” We’ll come back to the ballad mongers in a moment.

All of this was on scale more than double that of an average hanging would bring. Executions weren’t that common in Bedfordshire. In the next 25 years only three more took place in Bedford before public executions were outlawed. And it is suggested that the sheer numbers and boisterousness of the crowd at Sarah’s execution was a contributing factor to moving such acts away from public view.

I’ve read reports of how school children were kept in school all day that Saturday so that they would be protected from the crowd or from seeing the gruesome scene. Even in 1843 the appetite for such spectacles in certain corners of society was diminishing. But for others it was a chance to let off steam and enjoy themselves. And for some it was a way to make a quick quid selling gruesome souvenirs like the one sold in 2020 at auction or by producing ballads.

Broadside ballad

Sarah’s case crops up in relation to an historical curio which relates to executions and that’s broadside ballads. These were single sheets, the size of a broadsheet newspaper, that would print the details of the execution, the crimes committed and would proport to include the last confession of the criminal and poetry or a ballad that they had composed. And even though Sarah made no confession, wrote no poetry that we are aware of, and physically these broadsides had to be printed in advance of the execution, her alleged confession and poetry were sold by the thousands.

Only a fragment of the ballad remains, and this is what it says:

Farewell my friends and children dear,

Eternally farewell.

The pain I feel on your account

No longer on earth can tell.

A guilty wretch I am proclaimed

By vilest passions led

To murder child and husband too

My soul is filled with dread.

We can make out that arsenic is mentioned in the next stanza, along with Potton and then her parents good standing.

It’s the story the newspapers pedalled, put into verse probably by the daughter of the Bedford print makers. One academic believes this is a rare example of a broadside ballad written and printed by a woman.

And of course, it is all fake news. It’s the social media of their day. These ballads would be passed around, taken back to share with family and friends in the pub and at home. The song would be sung to a popular tune of the day and for a month or two or maybe longer sung by those who memorised it. Passed around the country, the terrible tale of the Potton Poisoner growing in gruesomeness with each retelling. And to be honest many of the newspapers towards the end were giving up on printing reliable information as well.

For the newspaper men it was as if the story had just been told so many times that no one checked their facts, So many newspapers when it came to the trial in July and Sarah’s execution the next month, claimed she had a daughter who she’d poisoned. Why they would transform a son into a daughter is a mystery, either laziness or maybe someone thought it made it just that bit more tragic. The names of key witnesses are mixed up and the general sloppiness seems to be because this case has already been done. There’d been three inquests and the newspapers are convinced of her guilt and are bored of reporting on it, yet they know it sells the papers.

Was she guilty?

As I said in the last episode, I don’t think there is enough evidence to be certain that Sarah poisoned either Simeon Mead or her baby Jonah. In fact, I think there is little evidence to implicate her. Statistically it is far more likely that baby Jonah got arsenic poison into his system by accident. And Simeon’s illness I think sounds like an allergic reaction rather than poison.

But should Sarah Dazley have been convicted of murdering William at trial? I do think there is enough reasonable doubt to not convict. There is so much doubt. But there is so much evidence missing as well; it’s hard to know for sure. If this was an accident where did the contamination come from? Why wasn’t that found or discussed in court? Other accidental poisonings were investigated, and the contamination was tracked down. Had too much time elapsed since William’s death to track down an accidental source?

The Gurry’s seem to have been present for a lot of William’s illness, but they clearly managed to convince a jury at both inquest and trial to their trustworthiness. They don’t seem to have been serious alternative contenders for poisoners whether by accident or on purpose.

Then there are the numbers, the fact that Sarah lost two husbands and baby in two years, all suddenly. Was this statistically significant for the time? Some contemporaries seemed to think so but a look at the death records show not dissimilar patterns to Simeon and Jonah’s deaths. But when you add William too, it does begin to strain slightly. But it’s not unheard of.

If she did murder all three, purely to get rid of them and move on to the next man or phase in her life, why did she not confess? She was supposed to be over dramatic and loved attention. Confessing would have generated that attention she craved.

And she did also appear to be quite religious. One criticism aimed at her was that she chose to go to church with her baby when he was poorly, rather than staying at home. Now it might not have been religious motivation that sent her to church that day, but she is also noted as reading the bible and singing hymns when Simeon is sick. She sounds like someone who did believe in God as most Victorian’s did, which meant it was in her interests to confess if she was guilty.

But I honestly can’t decide. I don’t think the jury should have convicted her, but I also don’t have an alternative explanation to put forward, other than the powders and pills given to her from Mrs Gurry were accidently contaminated with arsenic. And when you read some of the poisoning cases of the 19th century that include families accidently poisoning themselves over and over again! Never seemingly to learn from their mistakes, it does become apparent just how easy it was to poison yourself or another with arsenic back then.

What’s left behind.

After any shocking case like this the ripples are felt for many years to come, decades even. So, here’s some information about what happened to the people mentioned in this story.

Let’s start with the victims’ families first.

The Meads were always a small family. I find no trace of Anne Mead after this trial, maybe she married. Simeon’s parents also seem to vanish. Most probably they moved away and the name being a common one, it’s just hard to pick them out amongst the other Meads out there.

The Dazley’s were a bigger more established family in the area, and they do stay. Elisabeth and William senior’s sons, marry and have families of their own, still living and working on the farmland around Cockayne Hatley well into the 20th century. John is still alive in 1901 living with one of his 6 children.

William Dazley’s mother, Elizabeth out lives her husband and the last record we have of her, she is 66, living with the Herton family at Cockayne Hatley, they are prosperous tenant famers. Elizabeth is living with them as a nurse for their youngest, a little boy called William. It seems Elizabeth ended her days caring for a toddler with the same name as the son she so tragically lost.

And what of Sarah’s family? Her mother Anne and brother Philip live together on blackbird street in Potton for the rest of their lives. Anne as a nurse and Philip as an agricultural labourer. Philip never marries. It appears that this branch of the Reynolds family comes to an end. Sarah’s cousins on the other hand, the daughters and sons of the tailor Joseph Reynolds spread out across Potton and the country. Sarah has a cousin also named Sarah who is also a dress maker. She lives with her sisters in London throughout the 19th century, never marrying and eventually ends her days with a widowed sister and servant girl in a leafy part of south London.

And what of the Gurry’s Sarah and Ebenezer? They pop up in the records about 20 years after this incident and its in the criminal records. By now much older, Ebenezer is working as a collector of tolls and taxes, and he is successfully prosecuted twice for being overzealous in the collection of what is owed.

Dr Sandell has a large family, and his eldest son is also a William Henry Sandell who travels abroad, trains as a doctor like his father, and dedicates his life to treating the poor. He ends up working in Leighton Buzard in Bedfordshire, a doctor for the workhouse and the hospital treating the most deprived and impoverished and when he dies aged 78 in the early 20th century a lovely obituary is written about his life where they mention his large family back in Potton and how he followed in the footsteps of his father.

And finally, you’ll be wanting to know what happened to George and Mercy Waldock. I said they went to Australia after George’s uncle or cousin made the move in the mid 1840s. Well Mercy and Geroge end up living in a place called Bulimba. It sits on a curve of the south bank of the Brisbane River, on the land of the Yugarra people. I can’t find census nor birth and death records for Australia, that early in the 19th century, but I have found records of the land George was buying in this region. I also have records from the 1870s onwards of Mercy being issued and reissued a licence to run a pub. I believe Mercy passed away in around 1901 age 75. But from these breadcrumbs it seems she was the successful landlady of a pub for many, many years.

I wonder if the Waldock’s were tempted to make the move to Australia to escape the scandal that had engulfed them. It was a scandal enough to have a baby out of wedlock, let alone have that matter discussed in court and printed in the newspapers all over the country. It was another matter still for that information to be so widely known because you’d been engaged to a woman convicted of murder. Maybe the scandal just never let them be. It’s tempting to think that the Biggleswade Waldock’s took Mercy’s child with them to Australia to escape the scandal and then the couple joined them later, meaning Mercy was reunited with her child. Maybe with some more genealogy research we’ll find out.

Today

After episode one was released, I was contacted by someone with a former connection to the Chequers Inn at Wrestlingworth. The pub that hosted the three inquests into the deaths of Simeon and Jonah Mead and William Dazley. It is also likely that Sarah will have frequented that pub in less difficult times. It’s a short walk from where she lived.

This contact who wants to remain anonymous, said that during their acquaintance with the old historic pub, which was some time ago, memorabilia from the trial and execution of Sarah Dazley were held in the Chequers on display. There was even an old Victorian poison bottle and other bottles and jars which were said to have been left behind after the inquests. Now we know that the pill bottles seem to have disappeared, whether that was into the pockets of the coroner or left behind in the pub as a curio, we’ll probably never know.

But that wasn’t all that was left behind in the pub according to my source. They also said that the name Sarah Dazley was carved in stone in the cellar. And although there are a number of ghosts reportedly associated with the Chequers, one, a particularly malevolent poltergeist was said to be the spirit of Sarah Dazley. My witness described the following activity:

Doors would slam when there was no breeze or person to push them. Small objects would be thrown, and glasses pushed off the bar, people even witnessed the beer drip trays lifting into the air and flipping over. The mixer bottles would just shatter all over the floor when no one was near them.

But maybe the most frightening occurrence was the sound of heels walking across a stone floor, especially as the pub was carpeted at the time and many said the sound was the footsteps of Sarah Dazley walking towards the gallows.

Next time on Weird in the Wade

Something is stalking the water meadows and lonely lanes of Biggleswade. Something is seen slinking through residential gardens in the dead of night. Something is spooking dogs and their owners in broad daylight when they’re out walking.

Although it was some distance off it was very definitely a cat and it was very definitely not a domestic cat

I’ve spoken with two eyewitnesses and found two further reports of sightings in the last 20 years of non-native cats in Biggleswade, and I think I may have identified what at least one of the creature’s is.

We’ll explore other Bedfordshire big cat sightings and untangle what’s being witnessed. Are non-native cats really living in the UK countryside and if so, how did they get here?

We’ll also hear from a very special guest and his unique perspective on big cat sightings as I speak with the wonderful Welsh storyteller, Owen Staton.

And although the big cat of Biggleswade is definitely a corporeal beast, I’m also going to explore something a little more uncanny and the phenomena of phantom felines.

Join me next time for a celebration of all things feline, from big non-native cats to our beloved pets to those of a more ghostly variety.

End and Credits

Thank you so much for listening to this episode of Weird in the Wade, The Potton Poisoner. I have a feeling it may not be the last we’ll hear of Sarah Dazley. I’d like to record a short bonus episode exploring her legacy in folklore and analyse the ghost stories we have about her. Why do people believe that her spirit is restless? Why not the poor souls of those she is accused of murdering? What role do ghost stories and folk tales of poisoners like this play in our society today? But that’s for another time.

As always if you have any thoughts about this or other episodes or you have a suggestion for a future episode please do get in touch at the podcast email weirdinthewade@gmail.com or on social media we’re just about everywhere as weirdinthewade or there’s a link tree link in the show description. October’s Hallowe’en special episode is going to be about haunted pubs, so if you have a haunted pub story around Biggleswade, Bedfordshire or surrounding counties please do get in touch.

You can find the show transcript, notes and photographs on weirdinthewade.blog

And if you’ve enjoyed this tale of a Victorian poisoner or any of our other tales you can support the podcast which is made by just me, with voluntary help from Tess Savigear for music, by liking, following and reviewing the podcast wherever you listen. It really helps other people find the show. I know I say it every time but it’s true I promise.

You can also help the show by sharing and liking our posts on the socials. And I really do love hearing from you. The stories you share are brilliant and there is a lovely spooky community of weird in the wade listeners growing and ready to welcome you! It’s a great place to find recommendations for other interesting podcasts, blogs and social media accounts specialising in folklore, the high strange and general spookiness.

I also have a ko-fi page where if you are able to you can buy the podcast a coffee. The link is in the show description. All proceeds are ploughed back into the podcast so far being spent on a lav mic, travel costs, and actual cups of tea and coffee bought for those who have been kind enough to be interviewed for the show!

See you next time for a purrrfect episode of cat related strangeness.

Weird In the Wade is researched, written and presented by me Nat Doig

Additional crowd sound effects by Savigear and McOwen

Theme music and the Potton Poisoner theme by Tess Savigear

Cat sound effects from the pod cat Kasumi

All additional sound effects and music from Epidemic Sound.