Transcript and show notes

Intro

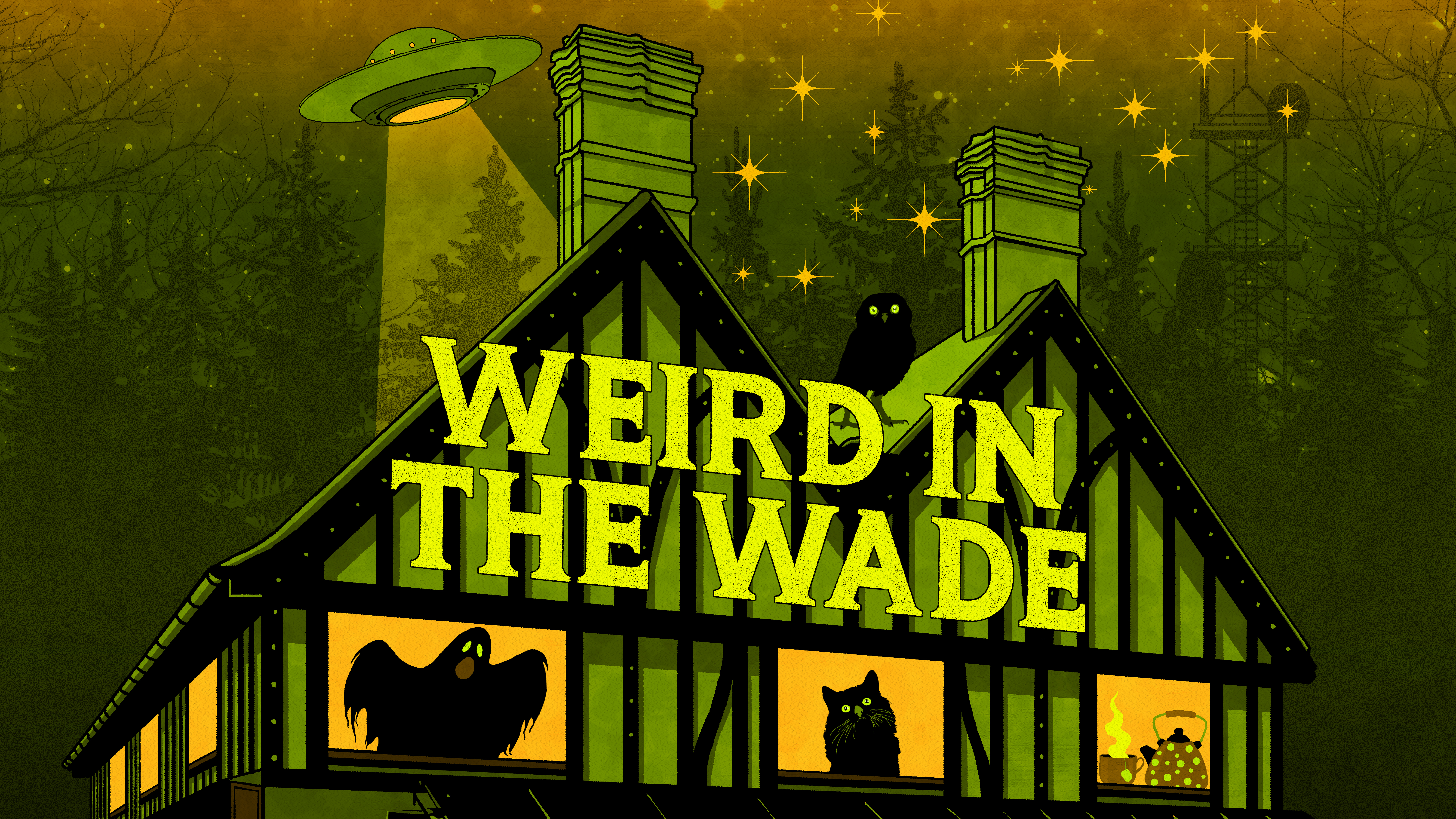

Welcome to Weird in the Wade’s first bonus episode!

Weird in the Wade is a podcast about all that’s weird, wonderful, and little off kilter in the town of Biggleswade in Bedfordshire.

We cover the kinds of stories that make you pause and ponder, and will speak to you where ever you are in the world.

Bonus episodes are an opportunity to delve a little deeper or peek behind the scenes of the main episdoes.

Dig into the past, or investigate a new theory, bonus episodes will be just a little bit different.

I hope to shine a brighter light, turn over another stone or untangle a different strand of the yarn for you.

As we uncover what was and still is weird in the wade.

Hi, I’m Nat Doig and in this bonus episode I will investigate the causes and consequences of Biggleswade’s great fire. Through my research with the newspaper archives I’ve discovered a conflicting but compelling potential new cause for the fire. Is the accepted narrative about how the fire started, taught to Biggleswade school children, reported by the council, and commemorated in the town, actually wrong? I’m hoping you’ll be able to make up your own mind after hearing the evidence.

This episode might not contain a ghost story (though do stick around to the end where there is some folklore including tales of a mythical beast to explore) but it is about uncovering facts that have lain hidden for the last 230 years. Oh, and there’s a dog in the mix too!

You don’t have to have listened to episode one of the podcast to enjoy this episode but you might want to give episode one a listen anyway. There is a mild spoiler just ahead if you haven’t already listened.

In episode one I investigated the story of Biggleswade’s haunted pound stretcher where I gathered witness statements from some of the women who worked in the shop. One of the theories put forward about the poltergeist activity reported there, was that it was caused by the ghost of a victim of the great fire of Biggleswade. In the main episode I investigated those claims and discovered – spoiler alert – that there appeared to be no actual deaths attributed to the fire. But I did discover some interesting things about the fire, that made me pause and want to find out more. And that curiosity led to me uncovering some new evidence.

What do we currently know about the fire?

Ask any school child in Biggleswade and they’ll tell you that the great fire started on the 16th June 1785 at the Crown Inn, caused by a lazy or incompetent servant throwing hot ashes onto dry straw. That the fire destroyed half the town and that is why the centre of Bigglewade lost all but one of its pre 18th century buildings (although the slightly less central St Andrew’s church is obviously older.) They might even point you in the direction of the Crown Inn and its mosaic commemorating the events. It was this narrative I used in my retelling of the fire in episode one. You can find the same story on the council and libraries websites. And in a fabulous booklet published by the Bigglewade Historical Society in 1985 to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the great fire. It’s mainly researched and written by Harold Smith the then President of the society.

Contemporary reports

As part of my research though, I wanted to find out if there were any contemporary reports still available about what happened. And luckily there are. It seems that our knowledge today about the fire comes from a handful of newspaper and journal reports from the time. And my search for evidence for the first episode uncovered a couple of articles that followed a similar pattern.

Here’s what the Northampton Mercury had to say about the fire on Monday 20th June just four days after it struck:

Thursday Morning last, about eleven o’clock, a most terrible fire broke out at Mr. Griggs’s, the Crown Inn, at Biggleswade, Bedfordshire; occasioned by a servant throwing some hot ashes into the yard, which communicating to a crate full of Straw, immediately set fire to the premises. The wind being very high, the flames with amazing rapidity spread to different parts of the town, and consumed near 200 dwellings, together with barns, stables, etc. a very considerable quantity of corn, hay, etc. with a number of hogs, and fat calves. The fire was not got under till near Six in the evening. Loss must be very great as many of the principal houses and inns were burnt down.

It was this account I used as a contemporary source during episode one.

For the bonus episode I tracked down more articles.

The Hereford Journal ran an almost identical article to the Northampton one three days after it, which only differs by saying its report comes via “a letter from Baldock” and it concludes with the lines:

The recent fires about us strike the country with terror.

More on the recent fires later.

Back on the 20th June 1785 the Reading Mercury ran a short article, they announce that the information was rushed to them by a messenger, which has quite a dramatic flair to it. I have visions of an out of breath messenger, horse still waiting to convey him on further, handing over a note with the bare bones of the story scratched on to it! The article is brief it says there was a fire and that the devastation it caused in Biggleswade was great, but not much more.

A very similar short article appeared in the Bath Chronicle and weekly Gazette three days later. Had the messenger moved along west from Reading to Bath with his news?

When researching for episode one I found one other mention of the fire from the Stamford Mercury printed on the 2nd September. It says that two ministers from the parishes at Stamford collected a considerable sum of money for “those sufferers of the great fire who were uninsured in Biggleswade.”

So with just a fairly basic search of the newspaper archives, remembering to use an f for the s in Biggleswade, as was the custom at the time, I found half a dozen articles which back the current narrative we have for the cause of the fire. There were two further articles that are more scant on detail but didn’t say anything different.

Newspapers in late 18th Century Britain

Although we are not in the Victorian heyday of British newspapers, by 1785 the reading public do have a number of weekly and even daily newspapers to peruse. One of the papers mentioned earlier, the Stamford Mercury, is one of the countries oldest, founded in 1712. And to give some context, the Daily Universal Register founded in London in the same year as our fire, 1785 changes its name three years later to the Times, and yes it’s that Times, which is still going strong today.

How the news was reported back then is in many ways different to today but also strangely similar. You find the same news articles or incredibly similar ones repeated in the different newspapers. It’s as if press releases have been dispatched to the various publication offices, as would happen today. And in a way that is exactly what was happening. Our letter writer in Baldock was sending letters to all the publications they could reach. The messenger with news in Reading would also be passing on the news to other places, like Bath. Was the messenger transporting the letter from Baldock? It’s hard to say as the articles that mention the messenger are the shortest ones with the least detail.

The late 18th Century may not have had the internet, email or even telephones but they did have messengers and the postal service, founded in 1660 though in 1785 they were some 8 years away from uniformed postmen delivering the mail. And so very much like today, reading through the newspapers, journals and periodicals of the time you find the same stories repeated, served up with a slightly different slant here and there, but basically the same. The majority of the reports into Biggleswade’s fire follow the same template even down to the words and phrases used. Based on either the letter from Baldock or the messenger’s missive.

Our Baldock reporter seems to be the person who first claims that the fire was started by a careless servant casting hot ashes on to straw at the Crown Inn. And in one article that follows the Baldock letter template, it is even speculated that this could have been committed on purpose.

A different take

So, I was quite surprised when I carried out an additional search of the online archives, and found a newspaper article in the Stamford Mercury from Friday 24th June, just over a week after the fire, that differed from the initial reports that were provided by the letter writer from Baldock or the messenger. It wasn’t easy to find this article because although it showed up in the search unusually there was no indication where in the newspaper the article was. So, I had to read through all the paper to find it!

The Stamford Mercury story has a different take on the cause of the fire, and it also provides us with additional and compelling information.

The report of the fire appears under the heading “Cambridge June 22nd “and after 5 short reports relating to Cambridge colleges and the clergy (Their priority was clearly to tell us that: the right worshipful Dr Cooper has been admitted into the antiquarian society, a vicar is moving to Oxford, a spinster of Cambridge is marrying an Oxford Don, and prizes were awarded to academics at 5 Cambridge colleges.) We eventually get to the real news. And here’s what the article says:

Thursday last at twelve o’clock, at noon, a very alarming fire broke out at Biggleswade, in Bedfordshire, which in a very few hours destroyed near one half of the town; the flames were beyond all description rapid, owing to the violence of the wind, and the quantity of thatched buildings. The poor inhabitants are very great sufferers upwards of eighty families consisting of near 400 men women and children having applied for relief. Very few articles of clothes or furniture are saved. The inhabitants being employed in the fields in hay making and other branches of husbandry. Their loss is upwards of £20,000 part of which will fall on two of the insurance offices. One hundred and twenty houses are consumed. Several barns, stables outhouses, warehouses filled with corn together with nine malting houses and a considerable quantity of malt. The houses destroyed were the best in the town, not one round the marketplace is left standing. A number of people who were working one of the engines were obliged to leave it in the flames the fire having nearly surrounded them. We are told the first appearance of fire was seen in a waggon, loaded with earthen ware, in the crown yard and is supposed to have been occasioned by some sparks falling from the lights while loading early in the morning.

This article does not follow the Royston letter template. It contains details that the writer from Baldock could not have known so soon after the fire. The estimated loss caused by the fire, the £20,000 figure is quoted later elsewhere too. The number of houses destroyed, and families affected. Eighty families made up of 400 men, women and children, all needing relief. The article makes it clear that the families affected lost not only their homes but everything in them, furniture, belongings and even clothes. And in many cases especially for the women working in lace making, their livelihoods too.

The fact that not a single building is left standing around the market square is utterly shocking. It was and is still a large space. Back then it was well known to anyone travelling from Stamford to London. The Stamford Fly was a coach that could be taken to London calling at Biggleswade, it’s advertised in a lot of the news papers of the time. Many of the well to do readers of the Stamford Mercury will have travelled to and through Biggleswade, shopping on that market square, staying at the Crown or Swan Inns. (Or many of the other smaller, cheaper establishments in the town.) Samuel Pepeys a century before made that very journey from Stamford to Biggleswade, buying a pair of wool stockings in Biggleswade and eating a fine meal of roast mutton there. In fact, Biggleswade was so well connected Harold Smith mentions in his booklet that coaches to and from London, that called at Biggleswade, linked the town to Boston, York, Lincoln, Hull, Oundle, Leeds, Newcastle and of course Stamford. He believes that at the time the fire started, passengers and horses from the Perseverance heading to Boston, and the Express from York on its way to London, were at the Crown Inn being fed and watered.

The fire engine question

The Stamford article provides us with additional information not included in other articles, about one of Biggleswade’s fire engines being sacrificed to the inferno as the flames began to surround those desperately trying to use it. It also answers a question I had been looking into when I wrote the first episode of the podcast, did Biggleswade have a fire engine in 1785? They were referred to as engines but they were really a pumping and hose device, nothing like a modern engine. Still, they were better than people carrying buckets! After the Great fire of London in 1666 towns across the country were encouraged to have their own engines. I couldn’t find mention of them in our current narrative about the events, and in fact Harold Smith in his booklet, speculates that Biggleswade didn’t have an engine although he knows that the south Bedfordshire town of Dunstable did at the time. This means that he bases his account on the assumption that the people of Biggleswade were reliant on just buckets and water. He laments that Biggleswade had not learnt from pervious fires or that of the terrible fire in neighbouring Potton just a few years before. But our Stamford article makes it clear that Biggleswade did have an engine, and in fact it says that the engine sacrificed to the flames was just one of the engines. And it makes sense to me that with Biggleswade doing so much trade from the coaches to and from London, and its famous market every Wednesday, it would have fire engines available. The population of Biggleswade may have been small but it swelled, ebbed and flowed through out the day and during the week as passengers and traders at the market came and went. Well-to-do passengers staying overnight in the inns would have expected a town to have the protection of a fire engine surely.

Flying sparks or careless human?

But the most remarkable information is that this article does not rehash the claim that a servant threw hot ashes on to the straw. Instead, it says lighting above a wagon throwing off sparks started the blaze. In this scenario I am guessing the naked flames of torches, lanterns, or oil lamps, formed the lighting above the wagon. They say that the waggon was carrying earthenware, which I assume means pottery. Now I’m guessing this made more sense to the readers of the time than to me initially. I had to have a good think about what a waggon loaded with earthenware would actually mean, as far as being a fire risk. Pottery isn’t something that is going to easily burn! But then I reckoned that to transport fragile pottery, was going to involve a lot of padding and protection. One thing I do know a little about is the history of the potteries in Stoke as my Mum’s family all worked in the pot banks or on the barges transporting the materials needed for production. And I remember reading that the canals made a huge difference for transporting pottery because they made for a smoother journey than a horse drawn cart rocking and lurching over the countries notoriously bad roads. If you wanted your pottery to arrive in one piece a smooth journey over water makes more sense than a rickety waggon.

So, I imagine this waggon of earthenware was padded out with straw and other material that was going to protect that cargo, and that was most likely incredibly flammable. The only thing that surprises me is that they say the waggon was loaded early in the morning, which also explains why there was need for light. Yet the fire was not spotted until late morning or possibly midday. Had it been smouldering away unnoticed for most of the morning then? This might explain why once it was noticed, it was too late and the flames had reached a critical temperature, all that was needed was the dreadful winds which whipped the flames through all the near by buildings. And the unlucky fact that the vast majority of the buildings were made of wood and thatch.

I did discover something else about this waggon. Something that confirms there was a waggon loaded with earthenware at the Crown. Harold Smith’s remarks in his pamphlet when cataloguing the losses from the fire, that:

There was also reported a curious item of the loss of £600 worth of earthenware and a letter speaks of earthenware being packed in The Crown yard where the fire started. Did Biggleswade manufacture or trade in the commodity two hundred years ago?

I haven’t found any evidence for pottery manufacturing in Biggleswade, though where pottery manufacturing happens there was always a risk of catastrophic fire as the dust in the factories was highly flammable in a similar way to how flour is a fire risk in mills. So, I think it’s more likely that this £600 worth of earthenware being packed at the Crown, is our waggon packed with earthenware. (Though £600 is an extremely large amount of money for some pottery even at the time I think.) I wonder if the pottery had been brought by barge to Biggleswade, the river Ivel was used like a canal at the time, and was being packed into a waggon for its onward journey? If you know anything about the price of pottery at the time or production in or near Biggleswade I’d love to hear from you as it might tell us just how much we’re talking about here! The letter Harold Smith is referring to is printed in the pamphlet and it brings together the earthenware and the servant throwing hot ashes on to the straw. I have no context for the letter, where it was found, Harold doesn’t provide any references for it and it’s produced without heading. Here is part of that letter dated Biggleswade June 24th:

You have no doubt heard of the dreadful fire that broke out at the Crown Inn here on Thursday night. I now send the particulars. The wind being very high the flames were communicated with astonishing rapidity to different parts of the town and consumed upwards of 120 dwelling houses, the dissenters meeting house, with several granaries, barns and stables, a large quantity of malt and grain, a great number of calves, hogs etc. A quantity of earthenware to the value of £600 is destroyed. It is not the power of language to express the horror of this conflagration which lasted til near six in the evening.

The letter speaks of the melancholy picture of ruins.

And finally, the letter ends bringing together the earthenware and the servant:

The fire at Biggleswade is said to have been occasioned by a servant girl throwing some hot ashes on some straw where people had been packing earthenware which soon catched a thatched house and spread itself almost instantly to others.

So which is it?

I’ll admit I was a little disappointed to see the servant mentioned again and in relation to the earthenware. So which was it? Was it a careless servant, later identified as a servant girl or was it sparks falling from lights? I think we can assume that the waggon of earthenware was involved and destroyed.

We have multiple contemporary sources, all newspaper or journal reports published within 4 -6 days of the event. And we also have this letter, which appears to be along the lines of the letter from Royston but written from Biggleswade 8 days after. I even wonder if the Royston letter writer wrote this letter too, having now visited the scene. There are similar phrase, and words used in both including the use of etc when listing items. To me the article in the Stamford Mercury reads very differently to the Royston letter and to this latest one. It has a very different more fluid style.

The early articles and there are multiple, support the servant theory, but I believe they’re all coming from the same source, the letter from Royston. It’s just that the letter is repeated in multiple publications. There are multiple reports but there’s still only one source.

So far, I have only found one account, the Stamford Mercury, proposing the sparks from lighting above the waggon theory but I wonder if the only reason this isn’t repeated, unlike the letter from Royston, is because the other newspapers and journals have already covered the story, so there’s no need to cover it again. The Royston letter got there first and so was repeated initially.

The frequency of fires

The severity of Biggleswade’s fire was terrible but fires in themselves were happening all the time. There are countless reports in the journals and papers just the same week. Whole sections are given over to reporting on the fires happening around the country. They list them in long columns, with details of place, casualties and damage caused. So, there’s always a new fire to be written about which might explain why after the flurry of articles based on the letter from Royston the story isn’t repeated. It is only picked up again some moths later when fund raising appeals are happening.

The letter on the 24th June, which mentions earthenware and serving girl is referred to by Harold Smith as just that a letter, not an article in a newspaper. It comes in a section about assessing the damage and so I wonder if he came across it whilst looking at records relating to damages sent to the insurers or the bank where charitable funds were being raised?

Mud sticks

So why did the careless servant theory stick and the lights over a waggon theory not?

I admit the simplest answer is that the servant theory was right. But something else could be going on here.

And, here’s my theory. When historians were researching this story any time before the last decade, finding contemporary source material was difficult. I’m amazed at how much contemporary source material Harold Smith found for his 1985 pamphlet. And it is this pamphlet that seems to be the main source of information about the fire used by the council, taught to school children and included on the mosaic plaque. Harold must have really put a lot of work into it. Newspaper and other archives have existed for a long time, but they have only recently been digitised. If you wanted to find information, say ten or more years ago you had to pore over actual copies of the journals, read countless pages of close typed information or fancy handwritten documents, just hoping to find something, anything about the fire. It was not an easy task.

Because there are multiple articles citing the careless servant theory but as far as I can tell only one mentioning the lights above the waggon, it was just going to be more probable that an article featuring the careless servant was going to be found. So, researchers were just more likely to stumble across the careless servant theory and print it. The odds are stacked against the lights theory from the start.

And maybe even at the time of the fire, for those not directly affected but living in fear of fire in general, believing that a careless or even malicious servant caused the fire could be more acceptable or even comfortable for them, than believing it was an accident. The type of accident that could happen anywhere at any time when you live in a world dependent on open flames for lighting and heat. You can protect yourself from foolish servants by being careful about who you employed, but you need an oil lamp or a candle to light your way and you have no other option. What would you rather believe? This catastrophe was preventable, or this catastrophe could happen to you and there’s not much you can do about it.

When humans are confronted by difficult, complex problems we often find it easier to blame a scapegoat and I suspect that servants and the poor in general were and still are always handy scapegoats. We feel uncomfortable seeing such devastation and reading about such loss. Some will find it easier to cope with those uncomfortable feelings by blaming, pointing fingers, and reassuring themselves that it couldn’t possibly happen to them. They’d be more careful, they wouldn’t employ such a careless maid.

Obviously now adays we’d ask questions about why no one noticed the fire smouldering? How did it get to the stage it was at, too late to prevent it spreading, when it was finally noticed? There’d be inquiries and reports and hopefully lessons learnt. But I can’t find any records of this type of activity happening or at least being reported on. There also doesn’t seem to be any court records of action taken against any careless servants. The papers of the time did report on the court cases and one like this about a famous fire would surely have been newsworthy. But I can’t find a thing. Harold Smith’s booklet includes the manor court records but they are focused on land and property that were destroyed and who owns what.

And so all of this makes me think that the more detailed report from the Stamford Mercury could be the most accurate one. There are details about the fire that could only have been given by a witness (the fire engine being surrounded by flames and abandoned) and that superior knowledge makes me think that their theory of it being caused by lighting casting sparks on to a waggon, was what caused the fire. A simple accident but a terrible one, one that would have struck fear into the hearts of everyone reading. And maybe that fear was what led to the other theory of the servant throwing hot ashes onto the straw being more readily accepted. It also serves as a useful lesson to children, housewives and servants everywhere. Dispose of your ashes carefully and only when they are fully cooled. It’s a complete story, it makes sense. The randomness of a fire being started by sparks from lighting just doesn’t have the same completeness to it. It’s not a satisfying explanation. There’s no hook to it.

The letter from the 24th June does make me pause though, if I hadn’t seen it in Harold’s book, I’d have been backing the light theory whole heartedly. We don’t know who the letter was written by, was it the correspondent from Royston or someone else? We don’t know who it was to either. Was it for a newspaper or journal, or to an insurer, bank or interested person? Harold Smith’s booklet contains extensive correspondence between the local gentry and a townsman called Dennis Herbert who was organising the appeal. It doesn’t read like his style of writing at all. I still think it might be from the Royston proto newspaper reporter, but I can’t say for sure.

What to do?

With this new information, the fire engine, the new theory for how the fire started, I wonder if the records should be updated? Should I tell the authorities and the local history groups of what I have found? Share my theories beyond this podcast? Or has the story of the careless servant tossing out the ashes been so ground into this tale that it can not be washed away? We’ll never really know the truth. (Unless of course someone invents a time machine but that’s a whole other kettle of fish!) I’m sure if Harold Smith was alive today, he’d be interested to know if not just for the fact that it appears that Biggleswade did have a fire engine. That the townsfolk had learnt from the previous fires but that the inferno was so terrible that at least one of the engines was destroyed.

What about the dog?

And that leads us on to the dog that I promised.

However, the fire started why did it get out of hand so badly? Yes, it could have been smouldering unnoticed all morning. Or it could have just been so fierce there was nothing that could be done about it. But there is a local legend as to why there was a delay in tackling the blaze and it goes like this.

The fire was spotted and immediately the person who saw it, let’s imagine that they were a young man who worked at the Crown, let’s call him George. Well George ran to get buckets of water. Maybe as he ran, he let out the cry for fire to warn everyone. But maybe not because maybe George thought he could easily extinguish the flames. He ran to the pump in the Crown Yard. Possible only meters away from where he saw the flames. George fills his buckets to the brim with water. And with the two heavy pails in either hand, sloshing with water, he awkwardly made his way back towards the seat of the fire. When out of nowhere running through the yard came what is described as a “mad dog” that ran between George’s legs, toppling him to the ground and sending the water splashing away nowhere near where it was needed. The dog scampers off never to be seen or mentioned again. It was because of this dog, that there was a crucial delay in tackling the fire. And just those precious few minutes made the difference between controlling the blaze and it is running a riot of destruction through the town.

It appears that this story is first mentioned a century after the fire by a Rev C H Chaplin who heard it from a resident of the town who says it was common knowledge and that the story tellers grandfather told him the story of the dog. So, it’s at least a third hand account.

I think the inclusion of the dog in the story of the fire is interesting for lots of reasons. Whether it happened or not. If it did happen, and I don’t see why it couldn’t have, then I’m not surprised it wasn’t mentioned in the contemporary newspaper reports, it was too soon for that kind of detail to surface or be deemed important. It’s the kind of detail you pore over later, when asking yourself: Could this have been prevented?

It’s also the kind of detail that can be added to a story once the pain and grief of it has ebbed slightly. Then it becomes something to comment on, to bring the tale to life, to be a lesson about keeping dogs under control maybe.

There is another reason why the inclusion of the dog in the story could have come about and why it became popular. It’s that age old tale of an animal having extra senses to humans. The story of the dog leads to the question: was the dog made mad by the fire? Was it aware of the fire before the humans? Was it fleeing when it could, because its animal senses knew all hell was going to break loose? Now adays we study whether animals can sense storms, earthquakes, fires and other natural disasters and warn their owners? The US CDC has an article on their website about whether prtd can sense disasters before humans and says in the case of fire yes they probably can . We now know that dogs have an amazing sense of smell and have been taught to detect all kinds of odours from sniffing out drugs and explosives to identifying disease. An ability like this would have seemed supernatural to the people of the time and during the 19th century when the tale became popular.

And finally, there is one other type of story about dogs and disasters, and that’s the myth and folklore around spectral black dogs or in east Anglia black shuck. A mysterious dog who in its most famous appearance during a thunderstorm in 1577 rampaged through two churches in Suffolk leaving scorch marks behind and killing parishioners who were praying. Obviously, there’s nothing in these reports saying explicitly that the dog was malicious or not of this world, it’s just described as “mad” and I’m not sure if mad was still being used in British English to mean angry by the 19th century, but I suspect they meant mad with fear or agitation in this case. But there is a long history of spooky stories across the British Isles about dogs appearing out of nowhere and being a portent of doom or disaster. I should add there are some more benevolent mythical dog sightings but that’s for another episode.

Whether the dog was actually there, or was added to embellish the story, I think it adds life to the tale. Illustrating how our lives turn on a six pence. The what ifs? The sliding doors moments. We’ll never know if the fire could have been put out if it had been spotted sooner, or if a dog hadn’t tripped a first responder.

The recovery

But what of the people of Biggleswade, how did they recover after the fire. The local Anglican vicar, by all accounts an elderly but kind man gave shelter in the church to those who could find no shelter elsewhere. Others huddled together in an old malting barn. A relief fund was set up and supported by the local landowners. Careful records were kept of who donated and how much. The Baptists also wrote to other churches and collected money for their flock, and their letter uses the metaphor of the inferno being like sin blazing through the populace if they are not looked after. It seemed to do the trick and more money was sent.

In less than a decade reports from the town by visitors make no mention of damage by the fire so it seems that rebuilding happened quickly. It would have needed to. Biggleswade depended on its trade through the coaching inns and would do so for another hundred years until the rail brought an alternative way to travel.

One aspect of recovery which isn’t mentioned by the primary sources is the psychological and emotional impact it had on the townsfolk, and I do want to cover that in another bonus episode where I’ll explore whether the case of a young Biggleswade man, being committed to the Bethlem hospital in London, just a few months after the fire, could be related in some way to it. But that’s for another episode.

Thank you

Thank you for listening. If you have any comments or information you’d like to share with me please get in touch through social media details can be found in the show notes.

Weird in the Wade, is researched, written and presented by me Nat Doig.

You can read the transcript of this episode and references to sources on the weird in the wade blog at weird in the wade.blog

The theme music is by Tess Savigear

All other music and additional sound effects are by Epidemic Sound.

Find weird on the wade on twitter and Instagram at weird in the wade.

Some useful resources:

History of newspapers in Great Britain:

Stagecoaches and coaching inns

https://britishheritage.com/travel/travel-englands-coaching-inns

The history of the Stamford Mercury